OPENING THE DOOR TO GOD AND EACH OTHER

The Joy of Interfaith Friendship

by Marcus Braybrooke

Friendship is becoming a subject of theological discussion, although the actual experience of friendship – or fellowship, which was the chosen term of Francis Younghusband, the founder of the World Congress of Faiths – is far more important. Reflection on friendship may help us see how we can both be true to our own faith identity and have a deep relationship with people of another faith.

London’s Mixed-Up Chorus was “founded on the belief that if we sing next to each other, we'll live well next to each other.” – Photo: Three Faiths Forum.

Aristotle asserted that friendship is “one soul abiding in two bodies.” The beginning of friendship is often discovering shared interests – for example the Three Faith Forum’s Mixed-Up Choir. This is why at its simplest, interfaith activities may just be getting people of different backgrounds together to visit each other’s places of worship or to share a meal and to enjoy each other’s company. It is good that increasingly we are asking each other to our religious celebrations. One Muslim group in Oxford has a Muslim celebration of Christmas, with readings from the Qur’an about Isa, Jesus – together with mince-pies and Christmas cake.

But maybe Aristotle over-emphasized similarity and agreement. It is said that Rabbi Yochanan and Rabbi Shimon bar Lakish shared a passion for the study of Torah, but they took intellectual and emotional delight in each other’s differing opinions.

I remember one remarkable example of this when I was working for the Council of Christians and Jews. It took place in the Jewish-Christian Manor House group. Two members of the group, Canon Anthony Phillips and Rabbi Friedlander, had publicly disagreed in the columns of the morning’s Times about the possibility of forgiving the perpetrators of the Holocaust. That evening they were both going to the same meeting. They entered the room together arm-in-arm. In the same way, if there is real trust in an interfaith group, there can be a vigorous exchange of views – which is rather different from what politicians mean by a “free and frank encounter.”

Several spiritual writers suggest that as a friendship deepens, a third presence is recognized. Jesus said, “Where two or three are gathered in my name, there am I in their midst.” One can think also of the transforming effect on Jalal ad Din Rumi of his friendship with Shams, an elderly Sufi, which led Rumi to grow from knowing about God to knowing God.

As we too come closer to the Holy One, we come to see God as a friend and more amazingly that God welcomes us as a friend. As the Sikh Guru Amar Das prayed to God, “Friend, may I always remain as the dust of your feet.” Or again, “O devotees, God alone is my friend and companion.”

As this happens, we learn to see others – all other people – as our friends. A remarkable example of this happened at a recent gathering at the Brahma Kumaris’ Global Retreat Centre, near Oxford. It was the final session and we were sharing our reflections. It was the turn of an American who was sitting next to a lady from Vietnam. As he began to speak he was overwhelmed with tears at having been in the American army during the Vietnam war, saying he was ashamed of what his country had done and was sorry.

The Cost of Friendship

I felt something of that shame on my way to visit Hiroshima. There I was met by a member of the Risho Kosei Kai new Buddhist movement. She was six years old when the bomb dropped from a clear blue sky. She told me of that terrible day – making her way home to find there was no home and that there were no parents. She talked about the many operations she had gone through and the way she was shunned by some Japanese people. But all this was without bitterness. When eventually we reached the Peace Bell, I stammered some apology, and she too spoke of the atrocities inflicted on Japan’s prisoners of war. In the silence we both felt a deep peace – the peace of God that passeth all understanding.

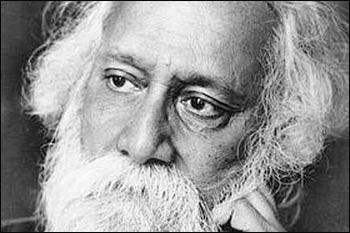

What we learn from our friendships, we should reflect in all our dealings with other people and see each person as a child of God. As the poet Rabindranath Tagore wrote, “When one knows thee, then alien is there none.”

On one occasion the Russian writer Turgenev tells of being in a small, low pitched wooden church. “All at once some man came up from behind and stood beside me. I did not turn towards him, but at once I felt that this man was Christ. Emotion, curiosity, awe overmastered me suddenly. I made an effort … and looked at my neighbour. A face like every one’s, like all men’s faces … the clothes on him like every one’s clothes.

“‘What sort of Christ is this?’ I thought, ‘Such an ordinary, ordinary man! It can’t be...’ And suddenly my heart sank, and I came to myself. Only then I realised that just such a face – a face like all men’s faces – is the face of Christ.”

Rabindranath Tagore was the first Indian to receive the Nobel Prize for literature. – Photo: AP

It is the face of the refugee for whom there is no room in the camp, the face of the asylum seeker drowning in the Mediterranean, the frightened face of the Ebola victim.

Jesus said what we do for the least of our brothers and sisters we do for him. Buddhists sometimes speak of the Buddha nature latent in each one of us. Tagore wrote: “Leave this chanting and singing and telling of beads ... God is where the tiller is tilling the hard ground and where the pathmaker is breaking stones.”

Perhaps the greatest gift of Mary’s and my interfaith journey has been enjoying the friendship of so many wonderful dedicated people of different faiths and nationalities. It is this that gives me hope for the future – that forgiveness, reconciliation, and friendship can heal the wounds of the past and allow us to create a world where every person is valued and at home.

This may seem a remote dream with all the violence and suffering in our world today, but that makes it even more important to affirm this. The abstract artist Naum Gabo continued with his work during the Second World War. When he was asked why he did so in a world that was breaking apart, he said, “We need to keep alive for the future the vision of our dreams of the world as it should be.” This is something each one of us can do and give hope to others by sharing our dream.

Header Photo: Unsplash