By Ruth Broyde Sharone

THE AMERICANIZATION OF MINORITY RELIGIOUS COMMUNITIES

Sisters Kavita and Hiral

My traveling companions on the train from Rome to Milan were two extremely good-looking young couples in their late 20s and early 30s – two sisters and their husbands – on their way back home to New Jersey after a ten-day impulsive Italian vacation. They had stumbled on a travel deal too good to pass up: round trip tickets on the Emirates Airlines from New York to Milan for $480.

Of Indian Hindu heritage, they all have Indian names: Poumil, Hiral, Sachin, and Kavita. All except Poumil were born in America. Sachin’s parents arrived in America in the 1970s. The parents of the two sisters, Kavita and Hiral, came in the 80s. Poumil and his parents immigrated in 1995 from the State of Gujarat in Eastern India, and they all speak Gujarati, one of the 130 languages and dialects native to India. The two young couples from time to time speak Gujarati amongst themselves, and the husbands also speak Hindi.

From the l., Kavita with a hand on her daughter Maya, Hiral, Poumil, and Sachin – Photo: House of Talent Studio

The couples’ decision to marry within the Hindu Indian community was not accidental. Their parents made it clear they expected their children to choose a mate from their own Hindu community, from Gujarat, and preferably with the same last name: Patel. They were not “arranged” marriages, but both couples willingly participated in traditional Hindu wedding ceremonies, wearing the prescribed elaborate clothing, shoes, headdresses, and floral wreaths.

Being a Hindu in America

Our conversation turned to Hindu practice in America and, in particular, their own spiritual practice. All four acknowledged that religious practice in their households was minimal and their connection to the Hindu tradition largely kept alive through their parents. The sisters have been vegetarians since birth; their husbands, however, eat meat. Every year they celebrate the ancient Hindu festival of Divali with their parents and the larger Hindu community; their parents diligently let them know the specific date of the holiday each year. Otherwise, they don’t generally attend their local Hindu temple for worship nor maintain a regular home practice. Both couples, though, have small altars in their homes and shelves for religious icons such as photos of Hindu gurus, statues of Ganesh and Shiva, and the like.

Do they plan to teach their children about their tradition?

Kavita and Sachin, the parents of two girls, ages one and three, said they haven’t thought about it. Poumil and Hiral, recently married, have not either. But all agree they want to educate their children about their ancestry and heritage. They have even considered speaking Gujarati to their children as one way to keep the connection alive. That would definitely please their parents, they concurred with a collective laugh and a slight hint of guilt, indicating how important the subject of cultural and religious identity is to their parents.

Nevertheless, my Hindu travelling companions all foresee the likelihood of their children inter-marrying. That does not worry them personally, as long as their children choose good partners, they emphasized. This sentiment brings up the challenge for devotees of all minority religions in America.

The Challenge Minority Religions Face

What is necessary, what is required to be able to sustain a minority religious identity in America, a country that affords minorities the freedom to practice their religion or no religion, as they choose? With the elasticity of choices that pluralism provides in an open society, how do devotees of Hinduism, Buddhism, Sikhism, Judaism, and Islam, for example – all minority traditions in America – maintain their separateness and identity when it may be easier to just be absorbed into the general American culture?

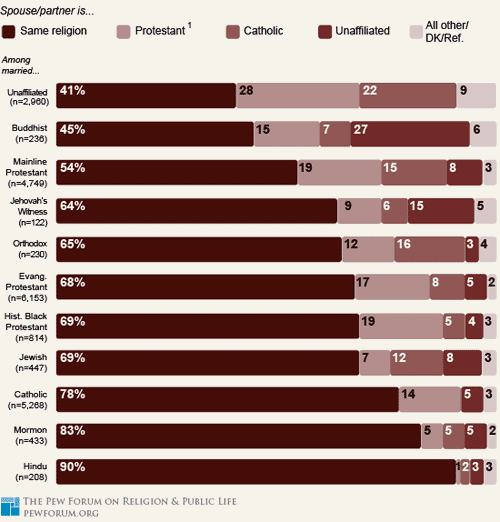

Statistics from Pew Research, for example, show an increasing percentage of assimilation among the Reform and Conservative Jewish communities – always a “red flag” to Jewish leaders who worry about the future of Judaism. Their fear stems from the fact that today there are less than 14 million Jews in the whole world, representing only 0.2 percent of the world’s total population, as compared to 2.2 billion Christians, 1.6 billion Muslims, 1 billion Hindus, and 1.1 billion who have no religious identification.

Interestingly, today many American Jews no longer identify themselves religiously, only culturally. Added to that is the fact that many young Jewish women and men don’t feel guilty about entering into interfaith marriage, something their parents and grandparents might have considered unconscionable. Mormons, Muslims, Sikhs, Jains and Zoroastrians in America, by contrast, seem to be keeping stricter religious boundaries around their children insofar as interfaith marriage is concerned, but that may also change as time goes by and the Americanization of their children intensifies.

Interfaith marriage, like economics, follows the law of supply and demand. A growing number of interfaith ministers are ordained each year. New York City alone now hosts four active interfaith seminaries.

Minorities in America have the freedom and luxury to openly maintain their dual identity. They feel comfortable establishing their distinctiveness through their garments and head coverings, by following special dietary customs, and by establishing religious and cultural schooling for their children: Hebrew Day School, Islamic Day School, or Chinese School, for instance.

Some of the younger cousins of the two Hindu sisters I met on the train study Gujarati in after-school classes. But basically the lives of these two Hindu American families are more mainstream than their parents’ generation, reflected particularly in their professional careers. Poumil, Hiral, and Kavita are pharmacists. Sachin is a “network architect” for IT. They are thoroughly modern Americans in contrast to their parents. Hiral and Kavita’s father, for example, is an engineer while their mother is a traditional housewife, though she no longer wears a sari.

So the ultimate question for those of us studying second-generation religious minority families and the establishment of interfaith cultures remains unanswered: Will America in the future continue to be home to multiple and distinct religious, ethnic, and cultural communities? Or will a new kind of American culture emerge where the hybrids will be the majority and the religious traditions of their ancestors largely studied in school and viewed in colorful museum displays?

Only time will tell.