By Beth Katz

APPROPRIATING THE BEST OF TWO TRADITIONS

I’m the daughter of second-generation Americans (SGAs). My four grandparents immigrated to the United States in the early twentieth century to escape desperate economic conditions and the grinding anti-Semitism they faced as Jews in Eastern Europe. Each settled in the Midwest United States and eventually in Omaha, Nebraska, where there was and remains a small but vibrant Jewish community.

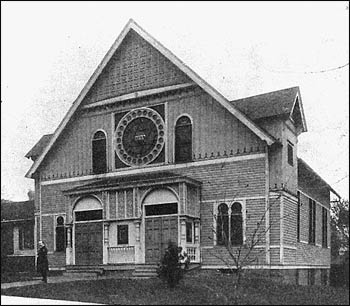

Congregation of Israel was the first permanent Jewish house of worship in Nebraska, built in 1884. – Photo: Jewish American Society for Historical Preservation

My parents are Baby Boomers who grew up in the 1950s and 60s. Their views about what it means growing up American were shaped by the era in the United States when they were raised and what they learned from their local Jewish community – particularly, how to navigate the dominant white, middle class, Christian culture. And the message then was pretty clear: if you want to be successful in America, you need to assimilate. This meant my parents never learned Yiddish, the primary language their parents spoke in Eastern Europe.

My mother and father both attended synagogue throughout their youth and had bar and bat mitzvahs (a ceremony thatmarks an adolescent’s transition into adulthood in Judaism). They went to public schools and tended to keep a low profile about their Jewish identity to avoid being harassed or bullied because of it. By the time they were adults, neither kept kosher. Jewish religious institutions and cultural centers became the places where my grandparents and parents truly felt comfortable being openly Jewish. Despite having gained significantly more rights and freedoms in the United States than they enjoyed in Eastern Europe, they still encountered pervasive anti-Semitism in this country and even more widespread ignorance about their religious and ethnic Jewish identity.

A New American Diversity

For nearly a decade as executive director of Project Interfaith in Omaha – an educational organization that grows understanding, respect, and relationships among people of all faiths, beliefs, and cultures – I have had many opportunities to work with Gen X and millennial SGAs of diverse ethnicities, cultures, and religious/spiritual identities.

I have been struck by how some of their experiences echo the struggles and realities my parents faced growing up in this country as SGAs in the fifties. But SAGs from the Gen X generation (born between early 1960s to the early 1980s) and the Millennial generation (early 1980s to early 2000s) are responding to these situations in distinctive new ways. One of Project Interfaith’s programs serving SGAs of all ages is RavelUnravel, a multimedia initiative that lets you hear individual faith stories and even tell your own.

RavelUnravel’s website features more than 1,100 short videos of real people from diverse religious and spiritual identities sharing how and why they identify religiously or spiritually. In the process they report stereotypes they have encountered and reflect on how welcoming local communities have been with their chosen religious, spiritual paths. Gen X and Millennial SGA voices are well represented, talking about religious/spiritual identity and their personal experiences.

SGAs in the United States today are a far more diverse group than previous cohorts. This diversity was in large part a result of the passage of the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965, which abolished the nationality quota-based system in favor of category-based immigration criteria, emphasizing skill sets and family reunification. These new laws allowed for a great influx of immigrants from Asia, Africa, and Latin America, leading to an unprecedented diversification of the American ethnic and religious landscape.

Social science research on contemporary second-generation religious minorities is limited but emerging.

For many second-generation non-Christian teenagers and young adults, religious institutions and cultural organizations continue to play a critical role, just as they did for my parents in creating a sense of community among immigrants and their children. They offer a common religious or cultural identity, helping SGAs navigate the dominant societal culture. For example, Sara mentions in her RavelUnravel video the impact the Muslim Student Association has had in providing her a support system and forum to speak with others about her particular faith in the midst of America’s religious diversity.

An early page from RavelUnravel’s website where you can listen to more than a thousand first-person faith stories.

Like my parents, many SGAs also encounter ignorance and stereotypes tied to both their ethnic and religious identities. This is not surprising considering the high levels of ignorance about religious diversity among the general American public, nor is this ignorance targeted exclusively at SGAs. Our RavelUnravel initiative shows it to be an unfortunate reality for individuals of numerous religious and spiritual identities. However, for young SGAs, the stereotypes and prejudice they face is often tied not just to their religious/spiritual identities but also to ignorance, assumptions, and biases that people hold about ethnicity, race, gender, and the countries from which their families have immigrated.

But unlike my parents’ generation, today SGAs are creating new ways to express the intersectionality of their identities. They have more choices, thanks to technology and social media, in how to respond to the stereotypes and biases that they face.

My parents downplayed their identities as Jewish Americans in order to assimilate into the wider culture. Today’s SGAs (as well as their non-SGA peers) choose to assert their multiple identities as Americans and as members of their respective religious/spiritual and ethnic communities. They are unwilling to emphasize one over the other, instead appreciating how each aspect of their identity informs and affects the other. One sees this in Maryanne’s video, where she explains how her identity and experience as a Roman Catholic American is largely shaped by her Mexican ethnicity.

In ways never imaged by earlier generations, widespread access to technology and social media makes it possible for today’s SGAs to stay connected to the countries from which their families immigrated. Social media allows them to cultivate a sense of community and solidarity with family and friends back in the home-country, simultaneously giving them a connection to their kin in America, as Sumaya's video indicates.

Personal formation by second-generation young people is also heavily influenced by the high levels of contact with people of different religious and ethnic identities, as Samira notes. This new, unprecedented diversity creates opportunities for all young people to craft their own unique take on their religious and spiritual identities. For second-gens, this typically means an identity related to the experiences and identities of their parents but also distinctly American. Manbir touches on this in his video as he talks about what it means to be a Sikh American.

Being a second-generation American in a small religious tradition seems to have certain universal aspects, today, 50 years ago, even a hundred years ago. Today, though, SGAs are charting new ways of articulating the layers and nuances of their identities and life in America. This new development is important because it allows us all to better understand who we are beneath the labels that we so easily place on one another and the incredible complexity and diversity that is contained within.