By Meji Singh

EXPERIENCING THE CREATOR EVERYWHERE AND IN EVERYONE

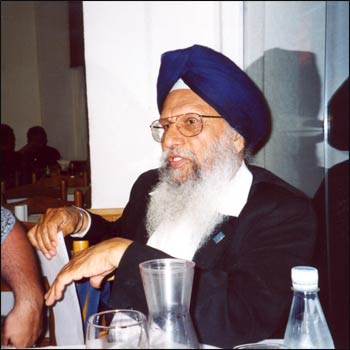

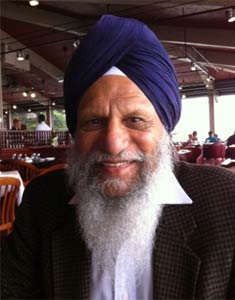

Meji Singh at an Interfaith Center at the Presidio luncheon in 2005. – Photo: ICP

Meji Singh did not grow up in the Sikh diaspora but in the religion’s homeland, India’s Punjab, in a family spiritually grounded in daily Sikh practice. But he has spent more than two-thirds of his life in the United States preoccupied with children and young adults, learning, and how to create mentally healthy communities. As a professor, consultant, spiritual teacher, organizer, faith and interfaith activist, he brings special gifts for what he calls behavioral consultation healing.

Just to be sure he wasn’t showing his age with this assignment, he sat down with a group of second-generation Sikhs to help write and edit an article about growing up a Sikh in America: Raman K. Kular, Preet K. Sabharwal, and Amardeep S. Sekhon. And beforehand he spent an evening with a dozen second-generation Sikhs from the San Francisco Bay Area.

To set the spiritual context, Meji observes that his professional work in clinical psychology is solidly grounded in root Sikh assumptions andvalues, the same perspective he brings in his devotion to faith formation and interfaith activism.

* * *

Sikh Spirituality

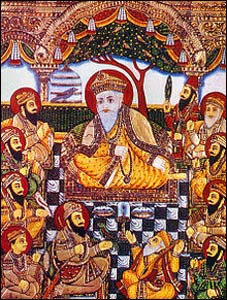

A 19th century painting of Guru Nanak in a circle of the 10 Gurus, with two friends at his feet, the one on the left a Muslim. – Photo: Wikipedia

Before talking about generations of Sikhs it may be helpful to understand the conceptual framework of Sikh spiritual practice. Baba Guru Nanak (1469-1539) was the first of ten Sikh Gurus, the spiritual founders of the tradition whose spiritual verse became the Sri Guru Grant Sahib, the essential Sikh scripture. Guru Nanak began writing his spiritual verses, or Gurbani, with the words “Ek Onkar.” It means there is one Creator who manifests Itself in its Creation. It is both imminent and transcendental. This spiritual unity, or the Creator, is called Naam, which literally means “the Name.” Sikhs also remember the Creator as Waheguru, the Wondrous Creator.

The question facing the Gurus was this: If the essence of all things and all beings is the same Creator, and if there is a spiritual unity in the universe, why is there so much conflict and suffering?

Before this Creation there was nothing and there was no sense of the other. Only the Creator was in deep meditation. When Creation came into being the Creator gave every being a sense of its individual identity. In Punjabi this identity is called Haumain, which means “I am” and is often associated with egotism and self-centeredness. Without Haumain, there would be no life, no vitality. But when Haumain takes over, becoming disconnected with Naam in a person’s life, the goodness of our lives can be corrupted five different ways: Kaam (sexual lust), Krod (anger), Lobh (greed), Mo (attachment), and Hankar (pride). Our impulses keep the world going around. But excessive attachment to Haumain, and losing touch with Naam, the source, the unifying divinity in every being, is the cause of suffering.

Before this Creation there was nothing and there was no sense of the other. Only the Creator was in deep meditation. When Creation came into being the Creator gave every being a sense of its individual identity. In Punjabi this identity is called Haumain, which means “I am.” Haumain has five impulses: Kaam (sexual lust), Krodh (anger), Lobh (greed), Moh (attachment), and Hankar (pride). These impulses keep the world going around. But excessive attachment to Haumain, and forgetting Naam, the source, the unifying divinity in every being, is the cause of suffering.

So Sikh spiritual practice promotes our connection with Naam. Traditionally we chant three poetical hymns every morning, about 45 minutes, along with shorter hymns at sunset and before sleeping. But spiritual practice is more than prayer. It includes seeking out the Sangat, or community of believers, listening to Gurbani being sung, called Kirtan, earning an honest living, sharing with others, and selflessly serving others, or Sewa.

In short, perceive and experience the Creator everywhere and in every one. There is no sense of duality. No discrimination on any grounds. Each of us is on this journey. Merging with Naam entails loving behavior, avoiding punitive value judgments, serving others, and appreciating, enjoying, and preserving Creation. Sikhs end every prayer with the words, “Nanak, by the Grace of Naam, always be in high spirits and let there be well being for every one according to Your Will.”

Second-Generation Sikhs in North America

Almost all immigrant acculturation studies show that the persons who are well adjusted in their parent-country culture are also well adapted in their host country. Second-generation Sikhs who come from stable families, whose parents are successful in adapting to American culture, tend to become high achievers, adapting well to an American environment while keeping their Sikh identity.

Most of them, it must be said, report that until they finished high school they were picked on and sometimes bullied. They were subject to racial slurs. But entering college they did not experience any discrimination. Their fellow students were more curious than hostile. About half the boys and nearly all second-generation Sikh girls have some college education. After 9/11, hostile behavior became more intense. More than 500 recorded hate crimes against Sikhs, and a few were killed.

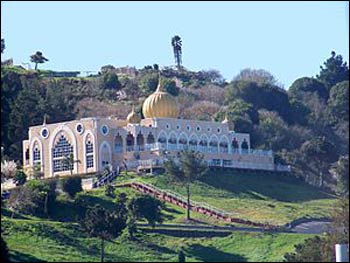

The Sikh Center of the San Francisco Bay Area, a gurdwara in El Sobrante, California – Photo: Wikipedia

Second-generation Sikhs have found it difficult to speak English at school and switch to Punjabi at home. Of the five identifying symbols Sikhs typically wear, the Karda, a steel bracelet, is the only one they retain. Only about 15 percent wear turbans, though those who do are very proud of it. Very few do recitation meditations, though they are familiar with Gurbani and recite it occasionally. They know the rules about “no dating,” though they often date. Over fifty percent of the Sikhs marry non-Sikhs.

A gurdwara is a Sikh sanctuary where the community gathers, worships, learns, and eats. Throughout the Sikh diaspora, almost every city where the Sikhs live has a gurdwara. The first created in America was started in Stockton, California. TIO published a wonderful second-generation Sikh story by a woman who grew up in the Stockton Gurdwara. Like their millennial peers in other religions, though, today the second generation has mixed feelings about the centers where they went to Sunday school and summer religious camps. They are ambivalent.

Services are in Punjabi, which most don’t understand. They perceive power struggles among the Sangat, the congregation, with members fighting to control their local gurdwara, even witnessing physical fights and lawsuits occasionally. Young people report “too much politics and too little religious instruction,” particularly among the separatists who want a separate Sikh state inside India called Khalistan. The Khalistan movement, besides promoting political folly, is contrary to Guru Nanak’s teaching, starting with the words Ek Onkar. You cannot be a Sikh and a violent sectarian at the same time.

In spite of all this, second-generation Sikhs are deeply committed to their identity as Sikhs. In spite of all the childhood negatives associated with gurdwaras, they are impressed by how they provide a place for socialization and maintaining Sikh culture. Young people are often very devoted and volunteer to prepare Langar, the blessed community meal following worship, for the Sangat. And they are ready for selfless service. Recently most gurdwaras have secured a simultaneous translation of prayers, projected on the screen, as Gurbani is being chanted or sung. During natural disasters they serve food to the needy and the homeless persons. Usually the Langar served is Punjabi food. But some gurdwaras, on occasion, serve pizzas and other Western foods that kids who grew up here like!

Sewa Tends to be Fruitful

In the spirit of Sewa, or selfless service, a series of institutions have been created by Sikhs born in America. They provide rich cultural resources to young and old.

- The Sikh Foundation was started in 1966 in Palo Alto, California, by Narinder Kapany, known internationally as the father of fiber optics. The Sikh Foundation’s mission is to preserve and display Sikh arts, literature, and history, and they work with large museums and universities.

Youngsters speaking at the international competition on Sikh history and Gurbani. – Photo: SHF

- In the mid-1990s the Sri Hemkunt Foundation was launched in New Youk by Sardar Shamsher Singh. Its mission is educating Sikh children and youth about their history, Gurbani and Kirtan. It holds an International Symposium and Kirtan Competition every year for five groups of children, ages seven to 25. Competitors from the U.S., U.K., and Canada create a 5-7 minute speeches on a particular subject and deliver them in their local gurdwaras. Winners compete in each of 19 regions, andregional winners are sent to the international competition.

- SALDEF, the Sikh American Legal and Education Fund, was founded in 1996. It’s mission: to achieve access and opportunity for Sikh Americans by protecting civil rights, building dialogue, deepening understanding, promoting civic and political participation, and upholding social justice and religious freedom for all Americans.

- United Sikhs is dedicated to disaster relief, human rights advocacy, and community empowerment.

- Eco Sikh is an international collaborative effort begun in 2010 seeking to preserve the environment in accordance with Sikh spiritual practice.

These and many more such creative programs are enriching Sikh life in America and the culture at large. Growing up here with families rooted in India’s Punjab and Sikhism is complicated, but young Sikhs seem to be doing well, a blessing for us all. Heidi Campbell’s story in this issue of TIO suggests that second-generation Sikhs retain their identity and traditional values close to heart. This much less scientific report completely agrees.