By Trebbe Johnson

FALLING IN LOVE AGAIN WITH WHAT WAS LOST

We love the places in our lives. There’s no getting round it, no trying to convince ourselves that we merely hold them in a kind of impersonal regard, appreciate them for their aesthetic qualities, or value them for those ingredients of industry we call “natural resources.”

The woods and streams we played in as children, the dogwood trees that flowered in spring on our college campus, the hills we hike that make us feel as if all of life, like the landscape itself, is exhilarating and full of promise – these places flow through our biographies, guide our ethics, shape our sense of how we belong in the world.

On June 22 people in Oregon, Easter Island, England, Bali, New York and other sites around the world will respond by actually GOING to those wounded places, spending time there together... then creating beauty in the form of a bird made of twigs, stones, trash or other materials supplied by the place itself. Join them and hundreds of others for the 4th annual GLOBAL EARTH EXCHANGE. You’ll be amazed how not only this place you love but you yourself will feel transformed!

And when they are damaged or destroyed, we grieve. Our hearts sink under the weight of grief, but how often do our rational minds attempt to rein in those inconsolable hearts? There is no way in our culture to cope with the demise of loved places, no way to say goodbye to them, and – especially important – no way to live with them now that they have changed so drastically. Too often those who express sorrow for places under assault are accused of loving dolphins (or trees or moss or beetles) more than people.

Yet how can we create a healthy, thriving future on Earth unless we open our hearts to the natural world in its brokenness as well as its splendor? A thoughtful person would not abandon an ailing friend simply because she can’t cure him. She would sit by his bedside, hold his hand, share stories of what is happening in each of their lives. So, too, can we attend to the ailing places we love. For it is by rebuilding our relationship with them that we empower ourselves to act on their behalf in fresh, creative ways and even fall in love again with places we had imagined lost forever.

My organization, Radical Joy for Hard Times, was founded to support individuals and communities in healing their relationships with wounded places by bringing attention and beauty there. Our practice, the Earth Exchange, entails simply going to a wounded place, sharing stories of what the place means to those who have gathered there, spending some time getting to know the place as it is now, and making a simple act of beauty there. Usually that act of beauty includes constructing a bird, symbol of transcendence and the ability to sing under all kinds of circumstances, out of found materials.

The benefits people discover through this simple and personal process are often quite surprising. Visiting wounded places, people discover that we are capable of facing situations that we had previously imagined would be too ugly or painful to endure. We find life thriving where we least expected it, and learn subtle but powerful lessons from nature’s infallible ability to persevere, adapt, accommodate. By making our act of beauty from materials we find on site, we realize, subtly but powerfully, that everything we need to be creative under any circumstance is already at hand and requires no outside “expertise.”

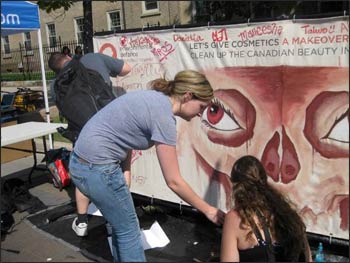

The mission of Radical Joy for Hard Times is to rediscover our connection with the places we love that have been damaged, by going to them and making beauty there. Environmental Defence Canada recently offered college students an unusual perspective on these subjects of beauty and damage. For their Just Beautiful campaign, artists visited four college campuses and invited students to create art out of cosmetics manufactured with toxic ingredients. Students learned about the ingredients in these so-called “beauty products” as they made beauty of their own in ways that called attention to the toxicity. Photo: Bradley Conrad, EDC

We recognize everything necessary to make beauty out of the non-beautiful is already at hand and that we ourselves are capable of making that transformation. Giving the work to the place, leaving it behind with the knowledge that snow, rain, tides, wind, or animals may carry it away, is practice in letting go and becoming emboldened to take the right action in the moment no matter what may result from it. Finally, the practice of creating this spontaneous work of art with others, no matter how young or old, able or disabled, spontaneous free spirit or meticulous planner, affirms that what happens to a place affects and is affected by everyone equally.

Federico Hewson participated in our annual Global Earth Exchange last June, when people all over the world go to wounded places to make beauty, and described his experience at Whitfield Mount, Blackheath, London. He chose to visit Whitfield Mount because it had been selected as a site for ground-to-air missiles that could be launched in case of an attack on the summer Olympics. “There is a power to nature that we forget and that we do not honor. In our intimate ritual, we re-membered our place in the natural world in the middle of South London. To honor these mounts or sacred dark caves as we need to honor the dark caves in ourselves and learn our wholeness.”

Very often, by the end of an Earth Exchange, people say, with some amazement, that they have fallen in love with this broken place. They say it of clearcut forests, industrial sites, and rivers polluted by chemicals from gas fracking. Creating beauty in a non-beautiful place transforms the recipient and the giver alike.

This article is republished from The Ecologist, January 21, 2013.