personal religious literacy

The Chinese Jews of Kaifeng (and what I’ve learned from them)

by Rabbi Anson Laytner

Kaïfeng Jews (Honan) during the end of the XIXe century, or begining of the XXe century — Photo: Wikimedia

For more than thousand years, there has been a Jewish community in Kaifeng, China, making it one of the most long-lived continuous Jewish communities in the world. Never more than a few thousand souls – and currently numbering a thousand at best – the Kaifeng Jewish community has excited interest far beyond what its population warrants. Much has been written about this tiny community, no doubt because of its “exotic” locale, its isolation from the rest of the Jewish world, and its inspiring story of perseverance.

Their really remarkable achievement was in developing a new kind of culture, fully literate interreligiously, that simultaneously allowed them to retain their own cultural identify for more than a millennium. Without a rabbi since the early 1800s and lacking a synagogue since the mid-1800s, the Kaifeng Jews managed to survive floods, wars, dynastic changes, rebellions, and revolutions to make it to the present day when, sadly, it is suffering the first suppression in its long history.

In Ancient Times

Jewish merchants first came to China from Persia by sea, rounding India and Southeast Asia, to reach China’s port cities, probably during the Tang dynasty. While some settled in the cities of Ningbo, Yangzhou and elsewhere, others made their way up the Grand Canal to the Yellow River, on whose banks Kaifeng sits. When peace prevailed in Central Asia, still other Jewish merchants traveled overland via the Silk Route to reach Kaifeng from the interior.

Kaifeng in Northern Song Dynasty – Photo: Wikimedia

Why Kaifeng? Because Kaifeng was perhaps the largest city in the world at that time and the capital of Song dynasty China, arguably the greatest empire of the era. Sometime between 960 and 1126, a Jewish community formed there. As these Jewish merchants settled in Kaifeng, they married local women, were financially successful, and after several generations built a synagogue in 1163 with government support.

The Chinese wives of these Jewish merchants adopted the Jewish way of life, as taught to them by their husbands, because Chinese culture is patriarchal, and women leave their birth families to become part of the family into which they marry. They would have been expected to carry out the rituals of their new household, in this case Jewish rituals. After several generations, community members looked ethnically Chinese (just as Jews elsewhere come to resemble their non-Jewish neighbors).

Although the use of Chinese patronymics by foreigners was not ordinarily permitted, the Kaifeng Jews were authorized to adopt Chinese names in appreciation of the role played by a Jewish soldier (or perhaps a physician), who in 1420 helped expose the treasonable designs of a member of the royal family. To this day all Kaifeng Jewish descendants belong to one of the following eight clans: Shi, Ai, Gao, Jin, Zhang, Zhao, and Li (with two clans using the name Li).

Free to integrate into Chinese society, community members worked as farmers, merchants, artisans, scholars, officials, soldiers, doctors, and the like. They assimilated to Chinese culture, just as Jews everywhere in the Diaspora assimilated to the culture in which they lived, even as they endeavored to follow Jewish laws and customs. In China they developed an interreligious culture borrowing from both Chinese and Jewish religious thought, again just like Jews elsewhere have done with the spiritual traditions in those countries.

Yellow River — Photo: Wikimedia

Unlike the Jews of Europe and the Middle East, though, who had to deal with Christian and Muslim anti-Jewish sentiment and persecutions, the Kaifeng Jews’ biggest problem was the Yellow River. Numerous times, this river, notorious for its devastating floods, damaged the synagogue complex, and each time the synagogue was rebuilt and Torah scrolls laboriously copied from salvaged texts. The sole positive aspect of these disasters was that the community commissioned four large memorial stones (stelae) to commemorate each major rebuilding. Thanks to these, we know how the community itself understood its history, beliefs, and practices.

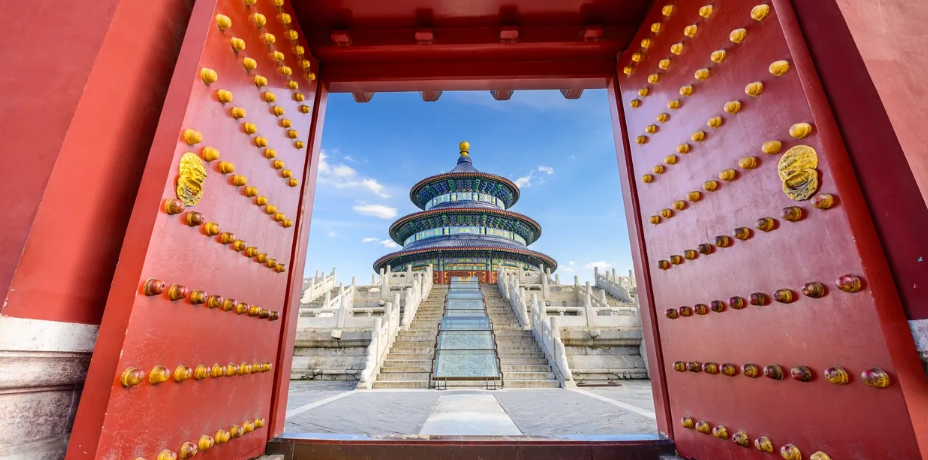

In addition, Jesuit missionaries visited Kaifeng in the 17th and 18th centuries. They drew accurate depictions of the interior and exterior of the synagogue and its grounds, detailed its holy books, and described how the people prayed. So we have a rather complete picture of the then-thriving community at its zenith. The synagogue complex, mirroring the architecture of Chinese temples, was several football fields in size and included a synagogue, classrooms, a ritual bath, a kosher butcher, and more. It was perhaps the largest synagogue complex ever constructed anywhere in the world.

The inscription on the 1489 stele tells us that Kaifeng's first synagogue was built in 1163. This synagogue, enlarged and refurbished as the need arose, was destroyed by flood in 1461. A replacement synagogue appears to have been consumed by fire around 1600. The third synagogue was swept away in 1642 by a flood caused by the deliberate rupturing of the Yellow River dikes as part of a plan for ending a siege of the city by rebel forces.

At least 100,000 people lost their lives in this inundation, including an undetermined number of Jews. Kaifeng's last synagogue, which was dedicated in 1663, served the community until the 1860s, when it was demolished or collapsed having suffered extensive flood damage. The congregation by then had become impoverished and weakened by over a century of isolation.

Europe ‘Discovers’ the Kaifeng Jews

Matteo Ricci — Photo: Wikimedia

The Jesuit missionary, Matteo Ricci, was the first European to meet a Kaifeng Jew, a man by the name of Ai Tian, who was visiting Beijing to take the civil service examination in 1605. Ricci in turn alerted Rome of the community’s existence.

Once Europe became aware of it, knowledge of the community played a role in the Terms Question in the Roman Catholic Church. It bolstered Menashe ben Israel’s case for the re-admittance of the Jews to England, and was employed by Voltaire to attack both Jews and Jesuits. But Jesuit links to the community ended in 1723 when the Qing Emperor expelled all missionaries from China.

It was almost 150 years later when British Protestant missionaries ‘rediscovered’ them, following Britain’s forcible opening of China after the Opium Wars. What they found was a community much diminished in wealth and education. Like the rest of China, Kaifeng had been ravaged by the Taiping Rebellion (1850-78). By 1850-51, poverty was so widespread that some of the surviving Jews illegally sold six of their Torah scrolls and sixty-three smaller liturgical books to emissaries of the London Society for the Promotion of Christianity among the Jews.

Great floods of the Yellow River in 1841 and 1860 left the synagogue complex in ruins while destitute Jewish families set up ramshackle shelters on the grounds of the synagogue complex. Around 1860, the synagogue remnants collapsed or were torn down and sold piecemeal. A half-century later the land itself is deeded to Canadian Anglican missionaries.

Photo: Wikimedia

Bishop William Charles White, head of this Canadian Anglican mission, convened a conference of Kaifeng Jews in 1919 in an attempt to revive the Jewish community, but not so much for its own sake as to give his mission a toehold among the general Chinese population. These Jews, they assumed, would be easier to bring to Christianity than their pagan neighbors and, once converted, they would be better able to convince other Chinese to join the Christian ranks than the foreign preachers could.

When British and American Jews learned about this and other missionary threats, various rescue efforts were launched, most notably one led by the Anglophile Baghdadi Jews of Shanghai with the support of the British Chief Rabbi and other leaders there. A number of Kaifeng Jews actually came to Shanghai to study in the early 20th century, and a Chinese Jewish teacher, David Wong Levy, was sent to Kaifeng. Unfortunately, this effort and others came to naught because Europe’s ongoing “Jewish problem” of the first half of the 20th century superseded these rescue efforts and commanded all the resources of the Jewish world be directed to this much larger crisis.

In Modern Times

By the turn of the 20th century, only memories sustained the identity of the Kaifeng Jews. Nonetheless, they leapt at any chance to revive their community, pleading time and again with visiting Western Jews and Christian missionaries for help in rebuilding their now demolished synagogue.

Member of the Jewish Zhao clan, Kaifeng, Henan, China — Photo: Wikimedia

Despite a profound lack of Jewish knowledge, members of this community have maintained a strong sense of identity in modern times, when awareness of their Jewish identity was all they had to transmit to the next generation. In censuses taken in the 1920s and early 1950s, many Kaifeng Jewish descendants wrote “Jew” as their nationality affiliation, an identity that was confirmed in local identification papers — testimony to the persistence of Jewish memory and identity despite great odds. Only in 1996 were they compelled to identify as “Han” Chinese.

When China opened up in the 1980s, and once again spurred by the activities of Christian missionaries in Kaifeng, the Sino-Judaic Institute and other Jewish organizations, connected with the Kaifeng Jews and began efforts to educate interested community members about Jewish history, culture and practices.

This productive and restorative period terminated in 2015 when President Xi Jinping imposed new restrictions on unauthorized religions. This effort, directed at Christian and Muslim groups, unfortunately (and perhaps inadvertently) swept up the Kaifeng Jews as well. Judaism is not an authorized, i.e., legal, religion for Chinese citizens nor are Chinese Jews considered a national minority.

As a result, the Kaifeng Jews’ school/community center was closed and SJI’s teacher expelled, community gatherings were prohibited, and museum exhibits documenting their history were closed. Seven years later, the situation remains the same-— yet still members of the community persevere, meeting in private and living as Jews as best they can.

Photo: Sino-Judaic Institute

A positive change in their status eventually will occur. One way out of the current impasse may be to return to Henan province or the Kaifeng municipality a degree of autonomy on this issue. The national policy on the status of the Kaifeng Jews can remain what it is, namely that there are no Jews in Kaifeng, only Chinese descendants, but the national authorities could permit Henan and Kaifeng the flexibility to adapt things to fit the facts on the ground.

This would be a return to the status quo ante in Kaifeng when, national policy notwithstanding, the descendants’ local papers identified them as Jews. But this, of course, would need to be accompanied by permission for the descendants to practice their unique form of Chinese Jewish culture.

Ideally China should herald the fact that it has never persecuted its Chinese Jewish community, much as it now celebrates its having served as a refuge for European Jews fleeing the Nazis. Ideally it should promote the historic Jewish presence in Kaifeng just as it does those in Shanghai and Harbin. Only good would come from such a decision. It would be an act of kindness for the Kaifeng Jews, economically beneficial for all of Kaifeng, and good for China in the eyes of the world.

** ** **

What I’ve Learned from Studying Chinese Jews

For many Jews, the Holocaust raises serious doubts about the traditional Jewish view of a God who can intervene at will in human affairs. Consequently, it also challenges the efficacy of intercessory prayer. Either God could intervene to stop the Holocaust and chose not to — for God knows what reason, or God could not, in which case our conception of God must change.

As a rabbi, I have long wrestled with this dilemma, both personally and on behalf of my people. I have taught, sermonized, and written two books on the subject, Arguing with God: A Jewish Tradition and The Mystery of Suffering and the Meaning of God.

Surprisingly, my solace came from a different direction: China. The personal religious literacy – that is, between ‘myself’ and ‘me’ – has gone into high gear since encountering and becoming literate about Han culture, the Jewish Chinese community, and the past thousand years.

As I struggled professionally and personally with Jewish spirituality — and simultaneously learning more about the Kaifeng Jews — I began to think that perhaps the Kaifeng Jewish materials might have something of value to offer the spiritually restless souls of our post-Holocaust, contemporary world. The more I studied the Chinese Jewish community of Kaifeng, the more I found comfort in their interreligious Chinese-Jewish culture.

Photo: Wikimedia

Let me note that many Jewish communities have attempted to meld their traditional Jewish concepts with those of their non-Jewish neighbors. The Tanakh (Hebrew Bible) itself is built upon and contains allusions to the beliefs of Egypt, Babylon and Persia. Centuries later, the Sages and Rabbis synthesized Hellenistic and Judean concepts to create Rabbinic Judaism (and early Christianity). In the Middle Ages and beyond, Jewish philosophers adapted Greek, Muslim and Christian philosophical ideas for their own use, and modern Jewish philosophy has been built upon the edifice of contemporary philosophical thinking. It was no different for the Chinese Jews.

Because they lived in China, the Kaifeng Jews borrowed from Daoist and Confucian thought. Like Jews elsewhere, the Kaifeng Jews wanted to have their faith and practices be understood in light of the dominant culture. In the Chinese situation, they were fortunate to live in a society that fostered syncretism, and which was indifferent to doctrinal differences in a way unimaginable in the monotheistic Middle East or Europe. Consequently, the Kaifeng community was able to embrace basic Confucian and Daoist concepts and relatively easily blend them with their own Jewish ones.

Script for Tian — Photo: Wikipedia

When talking about God, the Kaifeng texts use the term Tian, which is not a proper name (YHVH) or even a word meaning “God,” like the Hebrew El or Elohim. It is impersonal, even abstract. Like its Hebrew counterpart “Shamayim,” Tian is a word with a dual meaning, referring both to the actual sky and to a figurative or symbolic “Heaven.” Instead of using anthropomorphisms, the Chinese Jewish texts assert that Tian is a mystery, something truly beyond our comprehension. This is hardly an alien idea for it is precisely what some of the prophets, the Jewish philosopher Maimonides and the Jewish mystics taught as well.

The biggest difference between the Chinese Jewish “theology” and mainstream Jewish theology has to do with the concepts of revelation and God’s intervention in history. In traditional Jewish belief, revelation is something God gives to Moshe and, through him, to Yisrael and the world. In the Kaifeng texts, Tian, though ultimately a mystery, can be perceived both through the creative power of nature and through the Torah, both of which are called the Dao, or Way, of Heaven. Revelation is the attunement of the human being to the Dao, which is omnipresent and immanent. It is the role of the exceptional human being to perceive it, experience it, and to communicate it to other people.

In the Chinese Jewish view, it is through human endeavor and self-improvement — not unlike Maimonides’s views on the levels of the intellect and the prophetic mind — that an outstanding person like Avraham or Moshe can gain enlightenment and perceive the Dao of Heaven. In Avraham’s case, his enlightened state made him the first to “know” Heaven, and therefore he is honored as the founder of the faith. In Moshe’s case, his highly developed personal character led to his perceiving the mystery of Heaven and then to his composing the Scriptures and the commandments therein. But the revelation was theirs to achieve, not God’s to bestow. Absent from the texts is any substantive reference to Yisrael’s miraculous exodus from Egypt or its biblical years, or to God’s use of history and nature as either reward or punishment.

What emerges as most striking about the Kaifeng Jewish materials is their humanistic focus, much like that of Confucian thought. The ordinary person has only to practice the Dao as expressed in the Torah, i.e., the mitzvot, or commandments — honoring Heaven with appropriate prayers and rituals, respecting one’s ancestors, and living ethically — to put oneself in harmony simultaneously with the Dao of the natural world and the Dao of Heaven.

Kaifeng synagogue — Photo: Wikimedia

For the Chinese Jews, as for Jews everywhere, the mitzvot, the commandments, provide for Jewish continuity. They constitute “Jewish civilization” and, wherever Jews wandered, there too went the mitzvot. The Kaifeng Jews were traditionalists in their practice. They prayed three times a day, observed Shabbat and the holidays, and kept kosher and tried to live ethically. This is what sustained them despite centuries of isolation and the troubles they shared with other Chinese people.

The Kaifeng Jewish adoption and adaptation of the Chinese value ziran (self-awareness), remind me of the importance of personal spiritual development and the need for self-evaluation/self-cultivation as an integral part of observing the mitzvot. One is engaged in ziran not just for one’s own sake, but because one’s personal ethical behavior both shows respect for one’s ancestors and provides a model for future generations to emulate.

This sense of connection with the past and future was heightened for the Kaifeng Jews by their adoption of Chinese cultural norms of xiao (filial piety) and “ancestor reverence.” Ancestor reverence gave them a unique sense of being contemporary links in the chain of a proud and ancient civilization. It was a way of honoring and connecting with the past and emphasizing the responsibility of the present generation to prepare the way for the future. Although much more intense than normative Jewish practice, xiao has its counterparts in Jewish tradition too in values such as respect for parents and elders, and mourning customs such as observing the anniversaries of one’s parents’ deaths.

Photo: Pxhere

To summarize: Tian — Heaven, or God, exists, indescribable, although it is perceivable. Dao or Torah is Tian’s ordering of both the natural world and the human world. It too exists in some immanent way and is communicated to us by exceptional human beings. Accepting this, the ordinary person has only to practice the Dao as expressed in the Torah and thereby live their life in harmony with the Dao of Heaven. It is a faith that is firmly planted on earth and rooted in the proper doing of daily deeds (the mitzvot), yet its practice allows one to feel a sense of unity with the totality of existence, with past and future generations, and to aspire to a perception of the One.

What I ultimately absorbed from my study of the Kaifeng Jews’ theology was their emphasis on human behavior and on the ability of individuals to perceive an immanent Presence in the world. Their thinking provided me with an alternative to a system based on a transcendent God’s intervening in history, on observing God’s commandments (out of fear, or love, or both), and praying and waiting for God to intervene in history once again.

Header Photo: Sino-Judaic Institute