An Ancient Spiritual Practice that Never Grows Old

Mastering the Delicate Art of Rebuke

by Ruth Broyde Sharone

I am writing these words during the Ten Days of Awe, the period between Rosh Hashana, the Jewish New Year, and Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. As Jews, we are called upon to undertake a most challenging task during this period, to conduct what is called in Hebrew a heshebon nefesh, “an accounting of the soul.”

Photo: Needpix

We are enjoined to examine ourselves deeply for any behavior that could be considered a sin against God and then to appeal directly to God for forgiveness. However, sins against the human family, the sages tell us, have to be dealt with differently. The ancient rabbis knew it would be all too easy to get ourselves off the hook if we just asked God to forgive all of our sins en masse. The rabbis all seem to have agreed about one thing – as implausible as that might sound considering the diverse opinions rabbis hold about every line and verse of the Torah. They concurred that the correct way to handle transgressions committed against individuals is not to appeal to God but to approach the person we wronged directly – as uncomfortable as that might be – and ask for forgiveness.

Beyond this annual practice there is an even more delicate spiritual practice we have been asked to perform, one that can provoke genuine anxiety, lest it be carried out without the proper respect and exquisite care that is required. That is the practice of rebuke.

You shall rebuke your brother… (Leviticus 19:17)

If someone is not behaving properly, we are told to speak to them and correct their behavior. In the Talmud (a book of extensive commentary exploring the multi-layered meanings of the text of the Torah), it explains why we should engage in the art of rebuke. “You shall not bear a sin because of him.” If a person is not rebuked for bad behavior, for example, they may go out and do greater evil. Unfortunately, we have witnessed multiple examples of that in America over several decades. Following mass shootings in schools and public places, we have frequently learned that people who knew the shooter’s intentions didn’t speak up, but instances when people did, disasters were averted.

But there is a caveat when you intend to rebuke someone. The Talmud indicates a “proper” way to rebuke, because it is considered a sin to needlessly shame others, so we are warned to correct others without public embarrassment.

There are good reasons spelled out for this prohibition in Rabbinical literature because “if one acts out in public but is gently corrected in private, perhaps the two parties can still find a way to reconcile.” If the person who wants to give the rebuke doesn’t speak up, that person may begin storing resentment and eventually hatred.

In Proverbs 9:8, we are advised to consider ahead of time how our rebuke may land. If a person knows in advance that the rebuke will be ignored, he should keep it to himself. The actual text reads: “Don’t rebuke a scoffer; he’ll only hate you for it. But if you rebuke a wise person, he’ll love you for it.”

The Need to Rebuke

Rebuking, I have learned from personal experience, may be even more complicated than asking for or granting forgiveness. I vividly remember a scene I witnessed in 1994 in Jerusalem when Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, the founder of the Jewish Renewal movement, publicly rebuked an Israeli television reporter.

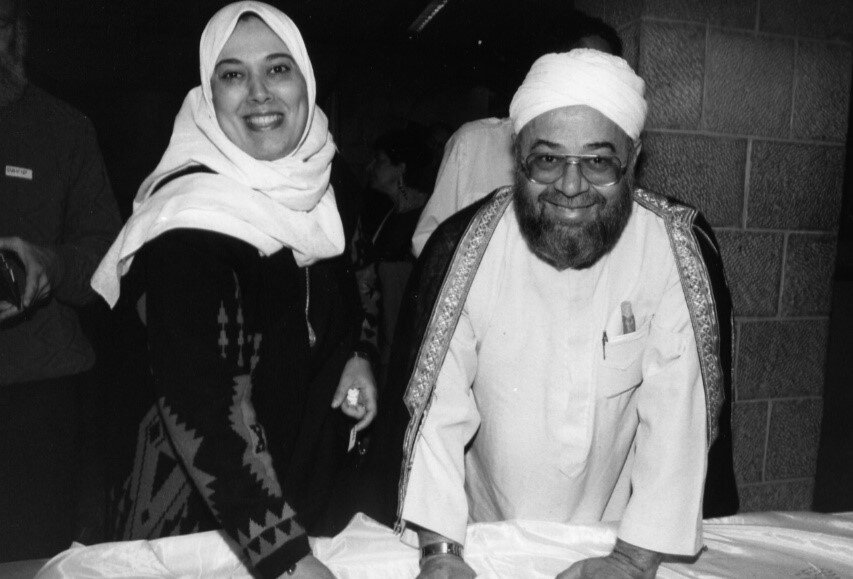

Mayor of Jericho, Rajai Abdo, and his wife – Photo: Ruth Broyde Sharone

At the time Rabbi Zalman was leading an interfaith Seder that I had co-organized with an African-American minister. The Palestinian mayor of Jericho, Rajai Abdo, and his wife were the guests-of-honor that evening in a gathering of some 100 participants from the US and around the world.

A reporter from Israeli TV arrived to document the event for CNN. The reporter began to grill the Muslim mayor about the ongoing conflict in the Middle East and the role of the Palestinians in perpetuating it. The mayor shifted back and forth in his seat, clearly uncomfortable. Suddenly Reb Zalman rose up from his chair. Looking like a Prophet of Old in his flowing white robe and white beard, he rebuked the TV journalist in front of the entire audience. It was a clear and unmistakable demonstration of “righteous anger.”

“The mayor and his wife are our guests of honor,” he said emphatically to the reporter. “They are in our home for dinner, and I take great umbrage with your line of questioning. This is not the time or the place to debate local politics. We are celebrating a Universal Freedom Seder together, not holding a public forum.”

Everyone was stunned and the room became silent. The startled journalist quickly apologized to the mayor and to Reb Zalman. Calm was restored, the mayor and his wife looked reassured, and the Seder activities continued, with sighs of relief that could be heard in the background.

The TV interview taking place during the Seder – Photo: Ruth Broyde Sharone

A short time later I saw Reb Zalman make his way over to the journalist and apologize for his outburst. He realized he had publicly embarrassed the journalist – recalling no doubt the admonition of the ancient rabbis – but, as he later explained to me, he felt compelled to protect the guests. I never forgot that incident.

Several years ago I felt called to rebuke an interfaith colleague of mine. I remember how difficult it was for me and how I nervously consulted with several other interfaith friends before I took the “leap.”

The colleague in question had created a new website which he touted as being an “oasis for peace.” Soon after, however, he began to publish extremely harsh anti-Israel articles, many of them reproduced from publications and writers known for their anti-Israeli and anti-Semitic tropes. When I questioned him about the true goal of his website, he defended his position adamantly, saying the media didn’t cover the plight of the Palestinians sufficiently in his eyes, and he felt compelled to do so.

He continued to publish provocative and often inflammatory articles online, alarming many of us in the interfaith community. To me they seemed particularly hypocritical in the light of his frequent insistence that he was a “peacemaker devoted to non-violence.” Why not include the other narrative for balance if, as you say, you are intimately involved in peacemaking? Shouldn’t you be willing to hear and present both sides of the conflict? Those were the questions I longed to ask him.

Finally, I could not hold my tongue. I decided to write him a private note of rebuke, rather than write comments on his website, because I didn’t want to embarrass him publicly. In my personal letter to him I wrote: “We, as peacemakers, have been asked to throw water on the fire, not gasoline.”

After reading my letter, he agreed to have an open discussion with several Jewish members of our interfaith community. At the meeting he was very defensive and unwilling to budge from his position. Like the others present, I was very frustrated, but we collectively decided to let the matter drop because we didn’t feel we could do anything further. In the end we had to acknowledge that it was his website and he was perfectly within his First Amendment rights to express his political opinions.

My hope when I rebuked him, however, was that he would recognize that calling his cyberspace platform “a hub for peacemakers” was in truth a masquerade. He was only willing to represent one side, the death knell for any peacemaking endeavor. Disgruntled comments I read on his website in the subsequent months corroborated my complaint, but I felt it was time to bow out.

The Challenge

I recalled that challenging interchange and my attempt at rebuke when I recently read a commentary written by the famous first-century rabbi, Eleazar ben Azariah, who said, “I swear by the Temple service, I doubt if there is anyone in this generation who is able to receive rebuke.”

Photo: Ruth Broyde Sharone

Rabbi Eleazar observed that people no longer accepted criticism as an act of love.” Instead of listening openly to a description of how they had acted inappropriately and then working to modify their behavior to remove that flaw, the object of rebuke would respond defensively by either ignoring or insulting the person who had highlighted the error.”

Rabbi Eleazar was accurate in his assessment. It is truly challenging to rebuke someone, even privately, because few souls are willing to own up to their bad behavior even if the criticism comes from a place of love or desire to restore justice. Nevertheless, I still believe there is great merit in the “you shall rebuke your brother” advice from Leviticus.

Even if I wasn’t able to change my colleague’s behavior, perhaps I planted a seed that one day would take root and eventually bloom. But beyond that possibility, I realize how important it was for me personally not to remain silent, even if I had to go out of my comfort zone to confront him. I’m glad I made that choice.

Perennial wisdom even after 20 centuries has not grown old.

Header Photo: Pexels