Toward an Ecological Civilization

Seizing an Alternative

by Philip Clayton

This is the story of the interfaith movement and climate change. It is also the story of a scholar of science and religion who gradually realizes that global climate change is the most urgent threat that humanity faces.

Rampant poverty, social inequalities, the unjust treatment of the global South, each of these is magnified ten or a hundred fold by climate disruption. I had assumed that a career of building bridges between the sciences and the religions would give me the tools to speak to the crisis and motivate others toward action. But over time I learned that a major change was necessary first.

The Limits of “Value Free”

For almost thirty years I had studied the multitude of ways that science and religion intersect: the alleged incompatibilities, the ways that both sides have attempted to belittle the other, and the most fruitful areas of overlap.

As the years went by, however, these discussions had come to seem more and more abstract. What do we really learn from relating “science in general” to “religion in general”?

Buddha meditating in nature – Photo: Benjamin Balázs, C.c. 2.0

The turning point came during the dozen or so years when I had the chance to work with religious scientists from around the world. The religion side of the science-religion dialogue gets far more interesting when you include all religious traditions. Where once there was abstraction, now a plurality of concrete beliefs opened up around me.

I watched Christians struggling to reconcile contemporary science with miracles and the resurrection, Muslims working to show how natural causes can exist when God is the sole cause of all things, and Hindus looking for scientific evidence that meditation produces better health. I saw that Buddhists who embrace the no-self doctrine and the interaction of all “causes and conditions” appeared to have an easier time making these connections. Jews, who are disproportionately represented among the world’s greatest scientists, also seemed to navigate the discussion with relatively low anxiety, perhaps because miracles and the supernatural are not necessary for Jewish observance.

In contrast to the beautiful plurality of religious beliefs and practices, I learned that science does not pluralize very well. True, different areas of scientific study raise different kinds of challenges for scientists (and for religious believers). But in most cases of disagreement, scientists possess and use empirical methods for deciding among them rather than embracing the plurality of thoughts and theories.

My bigger frustration with abstract discussions of science and religion is that they don’t do very much. Whatever values scientists may hold, scientific theories are supposed to be and largely are value-neutral. From science I learned a huge amount about the natural world, about its patterns and laws. I learned what is, but not so much about what ought to be. How can scientific facts motivate people to question their lifestyles … and then actually to live differently?

Putting Values Up Front

Bleeding Heart flower. “Inner transformation will come when our hearts bleed with compassion for earth.” – Photo: Jeff Jenkins, C.c. 2.0 nc nd

I don’t know a single religion in the world that is value-free. Most spiritual traditions are about living differently in the world. When a Buddhist monk practices metta bhavana, or what many call compassion meditation, he extends lovingkindness to all sentient beings. When a Jew speaks prophetically about injustices, or when she works toward the goal of tikkun olam (healing the world), she seeks to transform the world.

When a person of faith realizes the severity of the global climate threat, she can and should turn to the resources of her own religious or spiritual tradition. The same inner transformation that rabbis and roshis seek to foster in their followers can be a reorientation away from our addictions to comfort and consumerism; and the same social transformation that the prophets and spiritual teachers emphasize becomes a call to heed the suffering of those most impacted by the deteriorating environment. Isn’t Jesus’ observation a kind of social gospel: “Whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me” (Mt. 25:40).

When we place spiritual values first as a starting point and guide, the knowledge and predictive power of the sciences becomes our ally. The knowledge that is then available to us is staggering. We learn how and why the odds are astronomically against chance as the explanation for changing climate patterns. Literally dozens of different empirical measurements point toward the role of humans in changing the face of the planet: polluted air, undrinkable water, living soil becoming dead dirt. Multiple models predict the pace at which the various Earth systems, including ecosystems and species, will die.

Three steps are called for: first comes religious location and spiritual commitment; then clear, demonstrable knowledge about what has been and what will be if we continue to live as we do now ; and finally the goal of it all – transformative action. Values without facts don’t produce effective action. Facts without values don’t produce action at all. Spiritual values specify the goals we must achieve, and science helps us understand how we get there.

Toward an Ecological Civilization

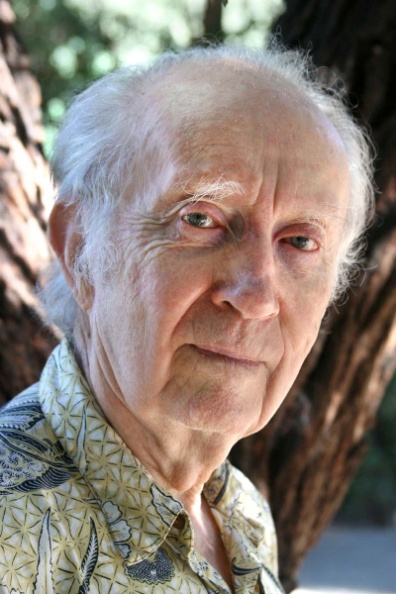

John Cobb – Photo: Wikipedia

In 2010 one of the most prophetic persons I have ever met, John. B. Cobb, Jr., started planning a massive conference on the planetary crisis. In case you may think that vision dies with youth, note that Dr. Cobb was almost 90 when he began the planning. Five years later, in June 2015, some 2,000 people poured into Pomona College to hear keynote addresses by major environmentalists from around the world. The majority of participants also joined one of 82 working groups formed to address the threat and how humanity should respond. The theme of this massive event was “Seizing an Alternative: Toward an Ecological Civilization.” Working with John Cobb after the conference, we then formed a nonprofit with that same name, “Toward Ecological Civilization,” or EcoCiv.org.

Photo: ctr4process.org

Month by month, the interest in creating an “ecological civilization” is rising. The name suggests that there may well be an end to modern civilization as we know it. It thus implies that today’s society is vulnerable; that our current social and economic structures may collapse under the weight of an increasingly hostile climate.

For example, today we read that the damage from hurricane Harvey, which flooded Houston and most of southeastern Texas, will top $120 billion dollars. How many such climate events can the government pay for before it is forced to withdraw its protection and support for the stricken communities? Without government support during and after crises, these communities will experience the kinds of raw suffering that many in New Orleans experienced after hurricane Katrina.

It’s a harsh picture. And yet, as frightening as the threats from climate collapse may be, people around the world are increasingly drawn to this notion of an ecological civilization. Why does it give hope? For one, the notion allows us, it requires us,to think beyond a potential economic and social collapse to what comes afterwards. The end of society as moderns have known it over the last 200 years does not mean the end of a meaningful life on this planet. In fact, what comes after the (inevitable) end of the modern era, and after the chaos has subsided, will be a higher quality form of existence.

Supertree grove in Singapore – Photo: Isen Majennt, C.c. 2.0 nc nd

A second source of hope in an ecological civilization is that it offers guidelines for action today. We know how to design sustainable forms of urban planning, transportation, consumption, agriculture, and other arenas. We know the kinds of educational systems, the kinds of social and economic structures, that are necessary to support these sustainable forms. This means we can begin taking the first steps now. In some cases, we can influence broader policies that have major impacts. But even where we can’t, we can begin to make the smaller changes in our lives and our communities that will gradually add up to transformation.

Many of the guidelines emerge out of the adjective ecological. Here the science piece is crucial. The ecological sciences present a way of viewing the natural world that is diametrically opposed to the old deterministic, “physics only” views. Understanding ecosystems gives birth to ecological thinking, which combines ethics and philosophy. And ecological thinking integrates beautifully with most of the world’s spiritual traditions; they speak the same language.

The struggle to blend science and religion, I suggest, is solved when one learns to organically combine the eco-sciences, ecological thinking, and ecologically-oriented spiritual practices.

Conclusion

Photo: Anne Worner, C.c. 2.0 sa

I have learned much from this journey. It does not give up on the importance of scientific knowledge. But it has taught me the importance of putting values up front. We must start with our location in the value-rich soil of our own religious or spiritual tradition(s), which provide our frame of reference, our point of orientation. When we have understood eco-spiritual values, we can then use scientific knowledge as a tool for understanding the world and for effective action. Eco-spiritual values usually require input from multiple religious traditions. Rich in input, they are rich in output. Eco-spirituality draws from the best of the world’s wisdom traditions to offer guidelines for living with, and through, the ecological threats of our day.

There are synonyms for ecological civilization: “integral spirituality,” a term used both by Pope Francis and Ken Wilber; creation spirituality, championed by Matthew Fox; new paradigm thinking or the “new story”; the “ecozoic age” to name a few. The call of eco-spirituality is to embrace all of these. It’s the call to come together as allies, working organically side by side for tikkun olam, for healing the earth.

Header Photo: NOAA