Demonstrating Need, Efficacy, and Outcomes

The Art of Interfaith Cooperation and the Science of Data

by Bud Heckman

Following Your Gut

There is something to be said for following your gut. But sometimes those instincts are nothing more than following your own biases and perspective on the world. They reinforce frames that don’t necessarily challenge or change anything.

How often do we let the data lead in our work? It is a slower process to do so. Much slower. But one of the strong and fair criticisms of the field of interfaith cooperation is that it is not grounded in or driven by research and evaluation. We need to change that.

Photo: JD Hancock, Cc. 2.0

We work on instinct, assumptions, and beliefs. We centrally focus on building relationships. Why? Because we see empathy-building between people with differences as the necessary heart of our work. Many of us see it as more art than science, more improvisation and tactics than planning and strategies. It is hard to quantify a changed heart after all. But not impossible.

We can and do take measurement of our work, both qualitatively and quantitatively. There is head counting as to how many come to our events, trainings, and meetings. There is pre-and post-surveying to ascertain changes in behaviors and attitude of participants. But it is much harder to say how that is having any real impact on our communities or our world. The use of data still doesn’t lead in interfaith the way that it does in other fields. That is a problem.

Following the Data

I have worked for three foundations in the field of interfaith and convene an interfaith funders group. Invariably, these foundations want to see measured outputs and outcomes. Most of those in interfaith-minded nonprofits whom they are seeking to help couldn’t honestly parse between the two, when challenged, because these nonprofits aren’t in the practice of having to demonstrate efficacy through measurement.

Chicago 2016 IFYC Interfaith Leadership Institute - Photo: Facebook

Yet one of the things most often demanded by funders and those who seek to scale and legitimize the work of advancing interfaith cooperation is research and data that demonstrates need, efficacy, and outcomes. Interfaith organizations that are getting more resources to conduct their work are those that are adapting to monitoring and evaluation, engaging the academy, and meeting the demands for correlative evidence.

Recently, the Einhorn Family Charitable Trust invested the largest grant ever issued in the field of interfaith relations, to my knowledge, by vesting further in their long-term partnership with Interfaith Youth Core. Their multi-million dollar investment’s main purpose is a long-term research study into the efficacy of the IFYC’s work with college students in the United States. This level of grant commitment should be a wake-up call to everyone interested in advancing understanding between people of different faith traditions.

Following the Researchers

While nonprofits advancing interfaith can and should do their own research, there are a host of researchers already collecting data about religion, values, social progress, peace, and even, in some rare cases, interfaith cooperation itself. The Hartford Institute for Religion Research (HIRR), the Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA), the Pew Research Center’s Religion & Public Life unit (Pew), the Barna Group (Barna), the Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI), the Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP), the Religious Freedom and Business Foundation (RFBF), and others already produce critical data and reports. There are also independent researchers like Paul R. Dokecki, Mark M. McCormack, and Hasina A. Mohyuddin at Vanderbilt University who have done in-depth surveys on understanding interfaith community initiatives.

Using this data creatively combined with an organization’s own research can help bolster how interfaith cooperation is seen as a field and funded. It can demonstrate efficacy of work and, where such efficacy may be lacking or unmeasured, suggest sharpening and re-arranging of tactics and strategy.

Using the Data

We can look closely at a few example pieces of data to draw out a story of what is happening with faith communities and with people of faith relating to one another to weave into the story of our own interfaith work. What follows are a few suggestions to get anyone started.

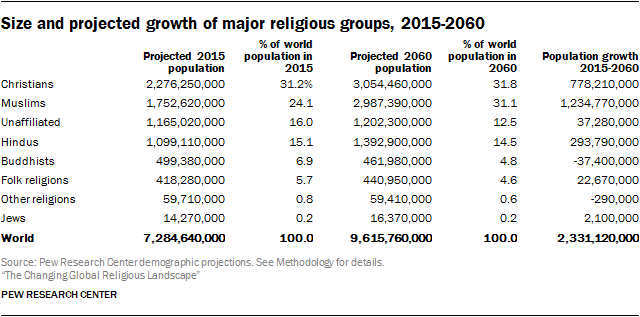

For a 30,000-foot global view and example, there is the The Changing Global Religious Landscape report just released in early April with the cooperation of the John Templeton Foundation as part of the Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures Project. This report projects that Muslims and Christians will draw even by 2060 in terms of world populations, each with around 3 billion adherents, largely owing to the fertility and death rates of the two traditions. It also suggests that the unaffiliated, who already account for 1.2 billion people, will grow largely by religious switching and are likely to decline due to very low birth rates, comparatively speaking. In fact, they are expected to be surpassed by Hindus as the third largest religious grouping as a result.

There are many other measures. One can also extrapolate data on tolerance and inclusion from the Social Progress Index by the Social Progress Imperative and on peace from the Global Peace Index, on terrorism from the Global Terrorism Index, and on pluralism from the Religious Diversity Index. There are also detailed country peace indexes with state-by-state breakdowns for those in Mexico, the United Kingdom, and the United States in the Global Peace Index.

Upending Misassumptions by the Numbers

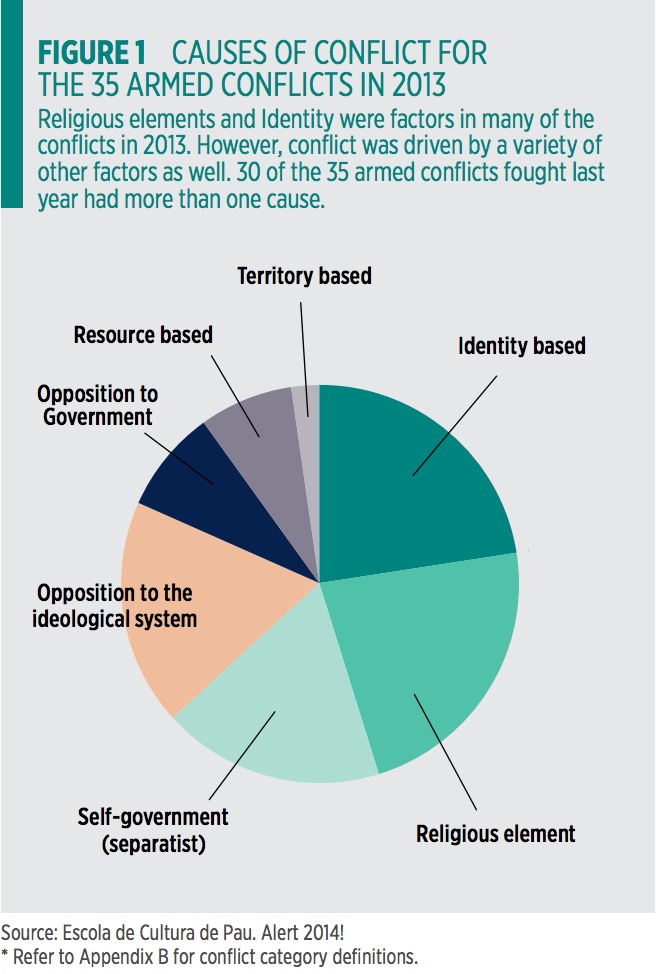

Given that religion is so readily and simply associated with conflict today, the joint work by the Religious Freedom and Business Foundation (RFBF) and the Institute for Economics & Peace (IEP) is probably the most important. Their research offers far different conclusions than the predominate media paradigm of a story of conflict between religions.

“Five Key Questions on the Link Between Religion and Peace: A Global Statistical Analysis on the Empirical Link Between Peace and Religion” is a product of the cooperation between the IEP and RFBF. This meta-level analysis on a wide scope of available research sources demonstrates, for example, that: religion is not a primary cause of conflicts today; intra-group conflict predominates over any supposed “clash of civilizations”; and both religious pluralism and religious freedom flourishing in a country leads to the greater likelihood of peace. Arguing these points with data is a lot more effective than sharing opinions and beliefs.

In the U.S. context, there are regular reports of various stripes by Pew, PRRI, including the important new American Values Atlas Survey, and there are the patterned reports from HIRR, including their survey of American congregations.

Here are some examples. Pew’s research shows that most Americans admit that they do not know any Muslims personally, and so, not unsurprisingly nor likely unrelatedly, the rate of unfavorable disposition towards Muslims has now surpassed any other category, including atheists, whom long held the lead. PRRI’s research shows rapid changes in rates of the unaffiliated with nearly 40% of all young adults now being categorized as “nones” or “nons.” HIRR’s research shows a recent decline in the interaction between people of different faiths in shared service and worship experiences, despite an overall increase in the rates since 9/11.

Marrying the Art of Interfaith to the Science of Data

To make the public argument for the relevance of the work of interfaith cooperation, we need to be well versed in these kinds of data sets. We also need to push for more monitoring, evaluation, and research in our own work. These two things will help bring more confidence into the interfaith enterprise. What will always be an “art” of interfaith cooperation will gain stronger footing with the “science” of data.

Even if our primary work is narrative, anecdotal storytelling about changed hearts and minds, we can still begin to supplement that with simple infographics about related data points, suggested correlation to greater trends, and a strengthened situation for our efforts. Eventually we can tell our stories statistically as well as wih narrative, and with any luck the interfaith movement will begin to move from walking to running in the right directions.