Confronting Fear with Love

A Trail of Thorns

by Jim Burklo

USC students with water jugs walk south towards the U.S.-Mexico boarder. – Photo: Jim Burklo

They walk north. We walked south.

Each spring break, I lead a group of University of Southern California students from various religious traditions down to “baja Arizona” for a week to experience the humanitarian realities along the U.S. side of the border with Mexico. We meet with progressive Christian activists – many of whom have been working for decades to prevent migrant deaths, assist migrants with practical help and legal representation, and advocate for legislative and administrative reform of our broken U.S. immigration system.

This past week, 11 of us stayed at Good Shepherd United Church of Christ in Sahuarita, Arizona – a local hub of border justice and humanitarian activism. On Tuesday, we went with the Tucson Samaritan Patrol on a hike up Wilbur Canyon near Arivaca, Arizona to place jugs of water on a migrant trail. For many years, this group and its partner, the Green Valley Samaritans, sponsored by Good Shepherd, have been doing “water drops” on the trails in order to prevent migrants from dying of thirst. The number of people crossing has dropped dramatically in recent years, and especially since the presidential election.

But we found evidence of very recent migrant crossings: clean-looking backpacks, “carpet slippers” that are tied over shoes in order to hide tracks from “la migra,” freshly-emptied tins of Mexican sardines. By the time they get to where we hiked, twelve miles into the U.S., migrants become exhausted and endangered. They begin to shed their belongings to lighten their loads as they move farther north. We were only a mile up the trail when one of our students bumped a water jug into a mesquite branch. Like so much of what grows in the Sonoran desert, mesquite branches are studded with sharp spines. A spine broke off, poking into her jug, and the water began to pour out. Another example of the many dangers that face the migrants as they move north.

At the “water drop” site, my students were very disturbed to discover water jugs, previously placed on the trail by the Samaritans, sliced with knives and emptied. Who did it? We don’t know. While “la migra” – Border Patrol officers – are trained not to do such acts of vandalism, they’ve been known on occasion to destroy the food and water left by the Samaritans. The anti-immigrant volunteer “militias” that faded away several years ago are now resurgent. ”Who could do such a thing?” one of the students asked me, incredulous.

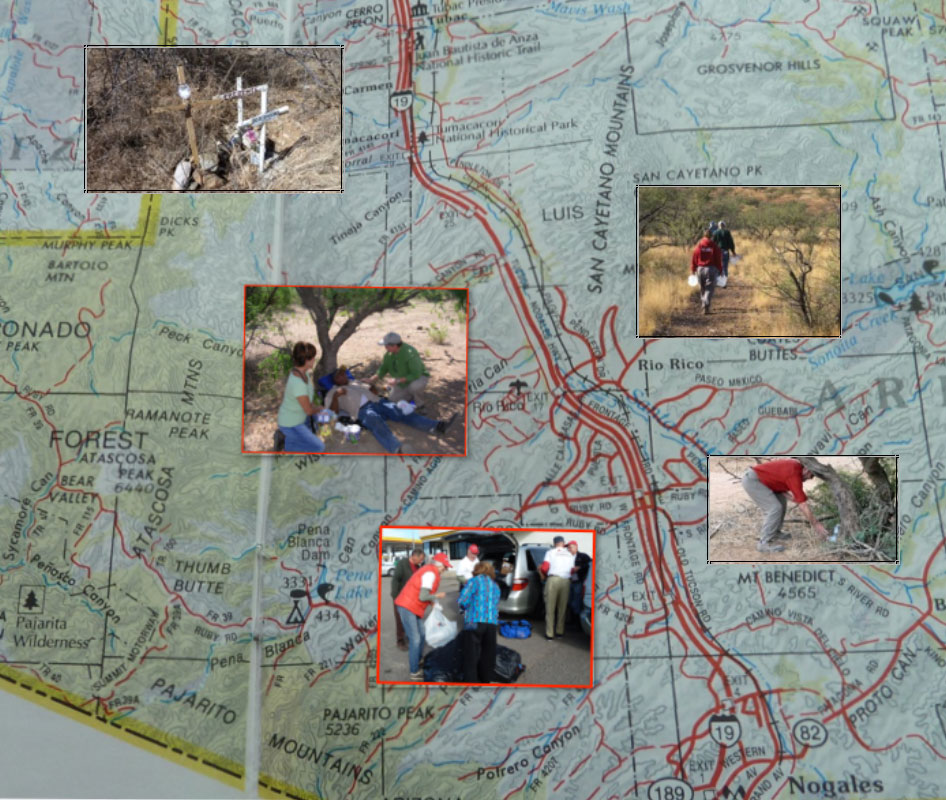

An Arizona map showing with photos telling the story of the Green Valley Samaritans and their work. – Photo: Green Valley Samaritans

“People are afraid,” said John Rueb, member of Good Samaritan Church and an organic garlic farmer in the borderlands. “So they lock their doors and stay vigilant and call the Border Patrol whenever they see folks they think are suspicious. But we never lock our doors. We welcome migrants who pass through our farm. They are always polite and appreciative. We give them water and some sandwiches and wish them well on their way. We aren’t afraid.” John hosted us at his farm for a chat with our group about what life is like for the people who live year-round so close to the Mexican border. It is a militarized zone where officers can enter one’s land without a warrant, where U.S. citizens must stop at a checkpoint and be scrutinized whenever they venture north. ”It’s almost like another country down here,” said one of our students.

Nothing better negates the idea of spending tens of billions of dollars on longer border walls and more Border Patrol officers than gazing out to the east from Lochiel, AZ. It’s a cluster of a few houses at the end of a 25-mile-long dirt road.

We went there with long-time border justice activist Father Ricardo Elford, one of the early leaders of the Sanctuary Movement in the 1980’s. Not a soul was in sight for 20 miles in the line of sight along the current porous border fence. If you doubled the number of “migra” officers overall, you might see one Border Patrol truck in that vast glorious expanse of golden grass, dark mesquite trees, and rugged mountains. A fence crossing that now would take seconds might take minutes over a big wall. But once over the border line, there is that 25 mile stretch of very rugged desert to cross on foot, just to get to the lonesome little Arizona town of Patagonia, well-patrolled by “la migra.” We already have a wall on the border, and it is called the Sonoran Desert. If it’s just for economic reasons, it is hardly worth one’s life to make a crossing that is more dangerous and daunting than ever. But when your life is your family “en el otro lado” – on the other side of the border – you might well take the chance.

A Tweeter’s digest of fear drives the dominant discourse about immigration in America. And the cure for this fear propaganda is love. The same divine power that propels people under fences, over walls, and through forbidding deserts can move citizens to press for saner, more humane policies at our border. Progressive Christians are living that love in southern Arizona every day. Let’s take the trail farther north, and spread the love deeper into America.

This article is republished from Musings by Jim Burklo on March 21, 2017.

Header Photo: The ‘walled’ U.S.-Mexico border at Lochiel, AZ, looking east – Photo: Jim Burklo