A Religions for Peace USA Interview

by Aaron Stauffer

Often in the interfaith movement, we speak about changes in the religious landscape and the impact these sociological, religious and political shifts have on the movement. Rarely, however, do we get the chance to hear from young leaders in the movement who spend time thinking about and challenging our expectations of what it means to be a leader in the interfaith movement today.

Several months ago, three other young leaders and I formed an intentional group – a community of praxis, we are calling it – to think through these questions together and to be a resource to one another. We discovered that the group is a huge asset in breaking down isolation that can exist between our organizations whose missions sound and appear harmonious. We wanted to dig deep into these challenges and see what would come of it.

To share some of the insights we’ve already had, Religions for Peace USA sat down with each of these leaders and asked them the same three questions

- What does it mean to be an interfaith leader in the 21st Century

- What does “leadership” mean to you?

- You’ve recently formed a community of praxis. Why did you form this group? And what did it do for you that other communities weren’t?

- A.S.

** ** **

RfPUSA: What does it mean to be an interfaith leader in the 21st century?

Jennifer Bailey: To me, 21st century interfaith leaders must possess a set of critical analyses to help frame their work.

First, we must recognize the intersectional nature of oppressive power. By this I mean understanding that “religious” conflict and violence rarely have to do with religion in and of itself, but are often the manifestation of a number of structural injustices. I think we have to cultivate a sharp analysis of the global economy and the ways it disadvantages the majority for the prosperity of the elite. And finally for this first point: race matters; gender expression and identity matter; sexuality matters; post-colonial paralysis matters. History matters – it’s about recognizing that our problems have a historical record and understanding that history will help us understand the problems and their intersectional nature better.

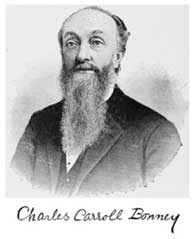

Because I’m an interfaith leader, this first point has a large bearing for me, helping me understand the historical context of the interfaith movement. The roots of the modern interfaith movement are often traced to the World’s Parliament of Religions at the 1893 World’s Fair (Columbian Exposition) in Chicago. The 1893 Parliament is viewed as the predecessor to the current Parliament of the World’s Religions. In his closing address to the gathering, Charles Bonney, who had the idea for a Parliament of religions, famously noted, “Henceforth the religions of the world will make war, not on each other, but on the giant evils that afflict mankind.”

If one takes Bonney’s declaration as the guiding aspiration for the modern interfaith movement, we must wonder whether we have lived into this vision. Much of the methodology guiding interfaith work through the 20th century was guided by models of “interfaith dialogue” – that is, people of different religious traditions being in conversation about differences and commonalities in theologies and religious practice. I would guess that the guiding hypothesis of this methodology based on the concept of “encounter” being the primary means of achieving Bonney’s vision.

Over the past ten or 15 years, organizations such as Interfaith Youth Core have begun to shift the interfaith paradigm away from “encounter” to one of “cooperation” through a service-learning model. The thought behind this is that encounter/dialogue is not enough but must be paired with collective action that facilitates lasting relationships. It should be noted that many of these groups see this work primarily as a sociological/democratic project rather than a religious one.

All of this will help us have a clear vision for what interfaith/multifaith work can be. In part this means seeing interfaith work as a means to an end rather than the end itself. And recognizing and affirming our theological/religious/ethical/moral differences as assets rather than a point of contention.

As a Christian, my end goal is the inbreaking of the Kingdom of God – a realization of a vision of the world as a just, compassionate, and peaceful place where all of Creation is valued for its innate dignity. Interfaith-oriented collaboration on social issues is one way of working toward this goal. But it also means that I have a challenge to dig deep into my own tradition when engaging others and working in the world for the Kingdom of God.

This is tough work, and requires us to believe that religions can be a force for good in the world while recognizing the histories that would cause others to doubt that it.

RfPUSA: So, define leadership for us.

Jen: Leadership is having the courage to risk one's significance to stand up for that which is right and mobilize others to achieve a shared vision. Civil rights pioneer Ella Baker once said that strong people do not lead strong leaders. I think she meant that everyone has the potential to speak prophetically and take action against injustice. A good leader is not the most charismatic person in the room but the person who is willing to help move others along in the face of uncertainty.

RfPUSA: You’ve recently formed a community of praxis. Why did you form this group? And what did it do for you that other communities weren’t?

Jen: One of the greatest paradoxes of the 21st century is the dual phenomenon of connection and isolation. We have more tools than ever before to engage each other yet thirst for deeper relationship. In our community of praxis I have found a space that fills me up through by giving me space to be vulnerable enough to ask questions and sit in uncertainty with a network of peers at similar stages in their life and career. It has been a God-send to have the space to be my most authentic self without fear of condemnation.