Seeing Jesus in a New Light

The Christmas Narrative Revisited

by Isabella Price

On December 25, Christians around the world will gather to celebrate Jesus’ birth with joyful carols, special liturgies, festive meals and gifts…Yet, what are the origins of Christmas and how did December 25 come to be associated with Jesus’ birthday? Contrary to popular belief, celebrations of Jesus’ nativity are not mentioned in the Gospels or Acts, and no hint is offered about a specific date or time of the year related to his birth. In fact, a careful analysis of scripture indicates that December 25 is an unlikely date for Jesus’ birth. Instead of being derived from any event in the Christian narrative, Christmas likely has pagan roots that trace back to the third-century Roman festival of the rebirth of the “Invincible Sun,” celebrated around the Winter Solstice when the increased darkening ends and the lengthening of the daylight hours begins.

Hauling in the “Yule Log” (1832) by Robert Chambers – Graphic: Wikipedia

In the northern hemisphere, our pre-Christian ancestors filled their homes and meeting places with candles, decorated evergreen trees, rang bells, sang songs – all to call the sun back into the sky. Long before the celebration of the birth of the child Jesus, the joy of new beginnings was celebrated at the time of the Solstice by the birth of a luminous “holy child” known by many names across ancient cultures. The magic of rebirth, light born out of darkness, is common to all people in northern regions. The name of this celebration of the young sun god’s birth has come down to us as “Yule.” The term means “Wheel of the Year” and refers to the endless cycle of changing light, temperature, and foliage as manifest in the seasons.

Hence, the birth of Jesus Christ is celebrated around the time of the Winter Solstice. We find no evidence in the canonical Gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John), though, that Jesus asked anyone to celebrate his birth. The decision of the Christian church in the fourth century to celebrate Jesus’ birth near the time of the Winter Solstice is a powerful expression of the same light symbolism. Jesus, born at the time of deepest darkness, announces the coming of the light. In fact, Jesus is the light in the darkness. The archetypal theme of light coming into the darkness finds another powerful expression in both the Gospels of Matthew and Luke — in Matthew with the star shining as a messenger to the wise men; in Luke with the glory of God appearing in the night sky as the angels sing to the shepherds.

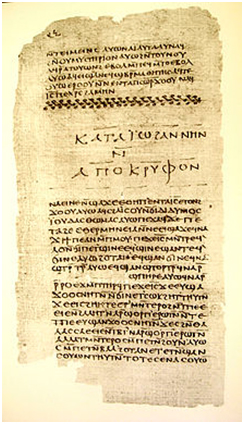

The light metaphor is even more emphasized in the non-canonical Gnostic Gospel of Thomas, where the Wisdom Jesus tells his disciples that they are “children of the light.” Gnostic Christians often referred to our true Self as a “spark,” and God as the divine light from which the spark emanated. Gnostics commonly believed that individual sparks of divine light had broken off from God and were trapped within the human body. In our ignorance, most of us humans are unaware that this spark of light exists within. Yet when we become aware of our true divine nature, we merge back into the divine light. The light metaphor in Christian scriptures also evokes the historical Buddha’s urging to “be a lamp unto yourself.” Similarly, Buddhist legend tells us that all the worlds were flooded with light at the time of Buddha’s birth. The term “enlightenment” eventually became a metaphor of liberation from the samsaric, repetitive cycle of suffering.

The beginning of the Gospel of Thomas (Nag Hammadi Codex II, folio 32) – Graphic: Wikipedia

The “spark oflight” metaphor also relates to the popular Christian notion of the Kingdom of God. In the Gospel of Thomas, Jesus uses humor to explain that the Kingdom of God is not “high up in the heavens,” nor is it to be found at the bottom of a watery abyss. In other terms, the Kingdom of God is not to be understood primarily as a specific location in time and space but rather as a state of mind that exists within us. Jesus follows this statement with a comment about the importance of self-knowledge, which is reminiscent of the Greek philosophic tradition. The fundamental principle of the oracle at Delphi was “Know Yourself.”

However, the path to self-knowledge is often an arduous journey. The second of Jesus’ sayings in Thomas reminds us, “let one who seeks not stop seeking until one finds. When one finds, one will be disturbed. When one is disturbed, one will be amazed, and will reign over all.” Self-knowledge inevitably involves inner turmoil. It requires that we face all unhealed and repressed aspects of our psyche that have caused so much pain and suffering in our lives. To reclaim both our true humanity and our intrinsic divinity, it is essential that we face our deepest wounds and own our “shadow” – both individually and collectively. Unless we process our shadow material properly, we will eventually project it on others. We may also note in this context that the mystical-esoteric traditions, including contemplative Christianity, have always viewed our psychological shadow-self and, by extension, “darkness” in a more positive light than the traditions of monotheistic orthodoxy.

In Christian orthodoxy, for example, light and darkness represent two opposing forces of nature: light is assigned the “good,” and darkness is assigned the “evil.” In contrast, mystics and sages across religions have viewed “darkness” as a metaphor of the great Unknown, death, and our own psychological shadow. Darkness is considered a gateway to inner transformation, rebirth, and illumination.

Similarly, ancient pre-Christian mystery cults centered on Goddess worship did not have a negative understanding of “darkness.” Particularly dark-skinned Mother goddesses may be viewed as symbolic representations of the night, death, and all the mysteries that Western culture has collectively repressed for centuries, due to the fear of death. As the great Sufi poet-mystic Rumi puts it so beautifully: “Darkness is your candle. Your boundaries are your quest. You must have shadow and light source both.” Similarly, the yin and yang symbol in Chinese Taoism expresses the ever-evolving interplay between the light and dark. Dark (yin) and light (yang) form a sacred circle with each containing a part of the other’s essence within itself. Yin and yang are not divided by a straight line, which would create a rigid and absolute polarity. Instead, they are separated by an S curve, suggesting that the distinction is fluid, alternating, and continually at play.

Beyond Dualism

The Taoist approach relates also to Buddhist teachings on dualistic views. Buddha Shakyamuni taught that the primary root causes of human suffering lie in our illusory sense of identity also known as the ego-centered self. This small conditioned self harbors the seeds for all types of dualistic views leading to a rigid and simplistic “either-or” approach of “us” versus “them,” or “good” versus “evil.” We encounter this viewpoint in all types of religious orthodoxy and fundamentalist movements. According to the Buddha, the ego-centered self creates the erroneous belief that we are separate and apart from everything else in the universe. The key is to re-discover our essential nature, our true Self, by engaging in the process of inner transformation.

Yin and Yang – Graphic: Wikipedia

In a striking resemblance to the teachings of the Buddha, the living Wisdom Jesus of the Gnostic scriptures emphasizes gnosis, self-knowledge and self-discovery, to a greater extent than does the more widely known “Christ of Faith” of the New Testament. From a Gnostic perspective, self-knowledge is knowledge of the divine. The Gnostic Jesus speaks of “illusion” and “ignorance” – not of “repentance” and “sin,” as in the canonical Gospels. The Greek term metanoia, commonly translated as “repentance,” literally means to go beyond the ego-centered self of the “small mind” into the “large mind” of our essential divine nature, as embodied by Jesus himself. Instead of being our “savior,” the Jesus of the Gnostic scriptures comes as a wisdom guide who opens the door to deeper spiritual understanding. The same approach can be found in the mysteries of ancient Egypt, where the importance of self-discovery and self-knowledge were equally stressed to initiates. Finally, we need to remember that the Apostle Paul himself also alluded to the awakening of this “hidden inner wisdom” in his First Letter to the Corinthians (2:7), a theme the Gnostics liked to emphasize.

While ancient pre-Christian religions and the early Christian tradition emphasized the importance of attaining wisdom and insight in their teachings, Christmas has today unfortunately become an expression of widespread commercialization that focuses primarily on personal gratification, excessive consumption, and gift exchange rather than on profound introspection more attuned to the spirit of Jesus’ message. We need to remember that the essence of the Christmas narrative is incarnation, the very idea that God has come into the world in the form of a human being known to the world as Jesus Christ. And his divine incarnation reminds us that, ultimately, our human nature is inherently divine and that we too have the potential of experiencing the mystery, the wonder, and the love of God in our own human bodies.

Header Photo: DeviantArt