By Marcus Braybrooke

TAKING CARE OF EACH OTHER

“Am I my brother’s keeper?” was Cain’s reply when God asked him where his brother Abel was. (Genesis 4:9) It is the same question being asked of wealthy nations by asylum seekers and migrants as they clamour to come in.

It is the same question that has been asked of those who have a comfortable life throughout my lifetime. Vegetarian meals at Madras Christian College, where I was a student in the sixties, were served on plantain (banana) leaves. Afterwards they were collected and thrown on a rubbish heap. But it was not birds who picked over the leaves but starving children hoping to find some grains of rice.

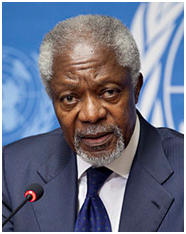

Kofi Anan – Photo: Wikipedia

A personal response is to “live simply that others may simply live” and to give generously to the needy. Indeed, as the Hindu poet Tulsidas wrote, “The one who you are helping is God in some disguise.” Jesus said that when we give food to the hungry, we give it to him. Each act of generosity affirms our shared humanity.

But when a billion people go to bed hungry? It is the international community that must answer Cain’s question. As Kofi Anan, former Secretary General of the UN said, the issues of poverty, the environment and terrorism carry no passports and transcend national boundaries. And religious boundaries. As Paul Knitter wrote in One Earth, Many Religions (1996), “Tables of bare bread and water are the tables around which religions should talk and plan action.”

Swami Agnevesh – Photo: Wikipedia

But what action? The Hindu campaigner Swami Agnivesh suggested in Subverting Greed (2002) that there are two radically different responses. “One is to place checks and balances so that the predatory and exploitative instincts in human nature do not become socially subversive. This approach is centred in law.” The other is to reject greed and material wealth and seek spiritual riches. The witness of those who adopt the second approach is a valuable reminder to others to question their priorities.

But it raises the question whether ‘wealth-creation’ is itself wrong, or merely its misuse. According to the third century Jewish sage Rav, “In the world to come we will face judgment for every legitimate pleasure we denied ourselves in this life.” (Jerusalem Talmud, Kiddushim 4, 12) The motivation for compassionate concern for others then becomes not guilt but thanksgiving. Gratitude for the blessings we enjoy makes us long for the day when all people share these blessings. As Jesus said, “I came that they might have life in all it fullness.” (John 10:10)

How then can we ensure that Globalization for the Common Good is really good? The task, already identified at the 1993 Parliament of World Religions, in Towards a Global Ethic – An Initial Declaration, is for faith communities to shape a just and moral framework for economic development and seek its implementation, an important part of which is in encouraging their members to make these priorities clear to politicians. In fact, many on-line petitions are having an effect.

In Tackling Poverty – A Global New Deal (2002 ), former UK Prime Minister Gordon Brown identified four building-blocks for a new global economic order:

Gordan Brown – Photo: Wikipedia

- Improvement in the terms on which the poorest countries participate in the global economy

- Adoption by international business companies of high corporate standards

- An improved trade regime so that developing countries participate on fair terms in the world economy

- Substantial transfer of additional resources from the richest to the poorest countries, in the form of investment for developments

There has been some progress. The faith-based Jubilee 2000 debt campaign led to the debt cancellation of some impoverished nations. The World Faiths Development Dialogue working in partnership with the World Bank has helped international bodies recognise that local faith leaders can play an important part in effecting change.

For example, the Sengalese law in 1999, to ban female genital cutting, was largely the result of a campaign by Tostan (a non-governmental group), which received money from the American Jewish Women’s Committee and gained the support of local interfaith leaders. More recently, faith leaders have taken effective action to stop the spread of Ebola. At the same time faith communities have helped international bodies rethink development priorities.

Several international bodies are seeking to promote good globalization, groups such as Transparency International, which fights corruption, and The International Business Leaders’ Forum, set up by Prince Charles, which campaigns for ethical standards in finance. Responsible businesses today now regularly have ethical audits.

Pressure on governments and international institutions can help: but passing resolutions is no substitute for helping members of faith communities to recognise that private morality is not enough. Only together shall we only create a world of compassion, peace, justice and sustainability” by “reclaiming the heart of humanity.” We are our sisters’ and brothers’ keepers.

The issues here are discussed more fully in my book a Heart for the World, (2005) and Promoting the Common Good: Bringing Economics and Theology Together Again by Marcus Braybrooke & Kamran Mofid (2005).

- Improvement in the terms on which the poorest countries participate in the global economy

- Adoption by international business companies of high corporate standards

- An improved trade regime so that developing countries participate on fair terms in the world economy

- Substantial transfer of additional resources from the richest to the poorest countries, in the form of investment for developments