A Different Kind of Power

by Paul Chaffee

Over the centuries religious leaders, like the rest of us, have run the gamut from exemplifying the ‘shadow-side’ of human experience to confronting the darkness and transforming lives for the good. Often this happens almost invisibly, when people quietly go out of their way to make a difference for the sake of love and a thirst for justice. Occasionally we are given leaders who, perhaps less than perfect, find the personal means, including great courage, to shine a light in the darkness and change the world.

Mahatma Gandhi, a Hindu, took on Christian England’s shadow-side not with arms but nonviolence, a value he shared with Jesus, a fact missed by the English. In doing so he freed his people and gave the West a lesson in the errors of faith-based oppression, an all-to-common reality we mostly hide from our consciousness, particularly when we are actually implicated. Martin Luther King Jr. and Desmond Tutu come to mind for speaking and acting on the hard truths, exposing our ethical rationalizations, and calling for a world that moves beyond denial and embraces the whole of humankind. Few such religious leaders, too few, come to mind today, for many reasons.

When the Story Doesn’t Get Told

Major media are part of the problem when they cover religion, though publications like Huffington Post Religion and Religion Dispatches are setting a higher standard and doing much better. It remains that Terry Jones, an itinerant pastor who called in the cameras for a Qur’an burning, gets ongoing global attention and coverage, while a story like the Moral Monday movement, perhaps the most important religion story in America today, has had little press to date.

Moral Mondays started in North Carolina a year ago. On a weekly basis, religious leaders and laypeople from all sorts of traditions began gathering on Mondays at the state capital in Raleigh to lobby, rally, and engage in nonviolent civil disobedience, all to demand ‘moral’ legislation. Hundreds have been arrested. On February 8 this year, between 30,000 and 80,000 (police vs. organizers’ estimates) marched on the capital to start their 2014 work. The movement has spread to Georgia and New York.

These religious leaders are vigorously taking on America’s shadow in the local political arena. Georgia’s Moral Mondays Coalition said the following in a press release:

“The Georgia state government’s right-wing agenda promotes corporate greed over people’s needs; denies healthcare to over 600,000 uninsured Georgians; has cut over $7.6 billion from public education in the past 10 years; accelerates income inequality by restricting workers’ rights and benefits; attacks women’s reproductive freedom; promotes bigotry towards the LGBT community; enables gun violence through 'Stand Your Ground' and 'Carry Anywhere' laws; and seeks to restrict our voting rights.”

The 2014 Moral March on Raleigh – Video: Courtesy of William Barber Channel

Outside of North Carolina, Georgia, and New York, the Moral Mondays movement is sitting there in plain sight (just google Moral Mondays), but invisible to most of us. To be sure, right-wing religionists have mastered and dominated the media cycle, and visitors to America can be excused for thinking that right-wing religion is more than an aging minority, a quarter or less of people of faith and practice; even less if you consider the spiritually independent. Moderate, progressive religious leaders frequently publish statements, ‘position papers,’ and requests for prayer about this issue or that – but they get barely any attention, much less influence, especially if it all stays on the page. Moral Monday leaders are taking it from the page to the street and starting to get noticed. If Dr. King or Gandhi-ji were with us, they would be supporters.

Amazing Exceptions: HH Dalai Lama and Pope Francis

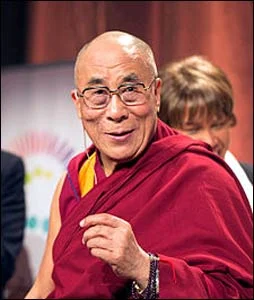

HH the Dalai Lama – Photo: Wikipedia

Despite the international paucity of highly regarded religious leaders, we have in our midst two exemplars who actively confront the shadow and in the process are inspiring global trust, influence, and affection – His Holiness the Dalai Lama and Pope Francis.

They are different in many ways, this Tibetan Buddhist and Catholic Jesuit. One we’ve known for a year; the other has been an influence for 50 years. One is an exile from his country and the spiritual leader of its people; the other is the head of the largest religious organization in the world, its first supreme leader from the Southern Hemisphere.

When I was a high-school student more than 50 years ago at a missionary school in north India, the Dalai Lama, then a young man and recently fled from Tibet, visited Woodstock’s campus twice. I’ll never forget the immediate, unlikely quiet that fell over several hundred teenagers one morning when he walked into Parker Hall and made his way to the front to address us. Every word he spoke (I remember my amazement) was written down to be kept in perpetuity. Several dozen books and many years later, he has been a nonviolent lightning rod on behalf of Tibetan liberation, without demonizing China as he is demonized by Beijing.

From this ‘powerless’ platform, living as an exiled refugee, the Dalai Lama has become one of the most loved and revered spiritual leaders on the planet, not only for Tibetans and Buddhists but anyone who appreciates Buddhist assumptions, goals, practices, and stories, and the man himself. A deeply rooted sense of justice, a spirit of humility, and his obvious goodwill flow out of the Dalai Lama like water from a mountain brook.

This core humility and an innate respect for ‘the other,’ whoever the other happens to be, is something the Buddhist sage seems to share with the new Argentine pope.

Asked by an Italian journalist who he really is, Jorge Mario Bergoglio, as he was named, began with “I’m a sinner.” Far from being a grandiloquent confession, he is straightforward about it all. As a sinner, he’s hardly in a position to judge those who are not like him, even from the papal throne. He accepts his own shadow-side, tells of his failures and what they taught him. So he’s not afraid of confronting the shadow publicly, addressing the dark realities in both the church and the world. He will wash the feet of prostitutes in prison, welcome the homeless at his birthday table, stand up for victims of the Mafia, champion the cause of immigrants and war victims, promote interfaith dialogue, and share his outrage at the superrich in a world where more than a billion individuals suffer terrible poverty.

A joyful face and frequent laughter in both these leaders is another measure of how much they share spiritually and why we pay so much attention to them.

Once upon a time religious leaders had huge temporal power, regardless of their spiritual lives. That has mostly faded away, which seems to be good, since religions that rule countries have a terrible reputation for intolerance and oppression. Today a different kind of power is called for, the power of authentic compassion, the courage to speak truth to power whatever the risk, and the influence of moral, ethical suasion. My personal sense is that new leaders who understand this (particularly among Millennials and women) are already in our midst, starting to make a difference, and that we’ll be hearing more and more of their stories.