Malaysia Struggles for Interfaith Harmony

One January afternoon earlier this year, twenty officers from Malaysia’s Selangor Islamic Religious Department appeared outside the office of the Bible Society of Malaysia. Demanding entrance, the officers confiscated more than 300 Malay-language Bibles imported from Indonesia, as well as ten Bibles in the aboriginal Iban language. The group’s president and manager were detained at a local police station. Later, after both were released, the society’s president stated that they would continue importing and distributing Malay and Iban-language Bibles in spite of the seizure.

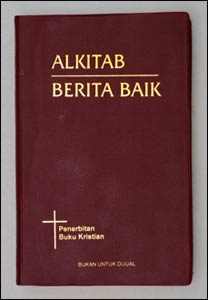

A Malay language Christian Bible – Photo: WikipediaThe reason for the raid boils down to the use of a single word: “Allah.” The offending texts had contained the Arabic word for “God,” and the confiscation was merely one event in a long saga that began in 2008. Back then the Herald, a Malaysian Catholic newspaper, was prevented by the Home Ministry from using the word “Allah,” even though it is also the usual word for “God” in the Malay language. Challenging the ruling, the Church brought the case to the High Court in the capital (Kuala Lumpur) and won in December 2009 after the court overturned the ban and upheld the church’s constitutional rights.

A Malay language Christian Bible – Photo: WikipediaThe reason for the raid boils down to the use of a single word: “Allah.” The offending texts had contained the Arabic word for “God,” and the confiscation was merely one event in a long saga that began in 2008. Back then the Herald, a Malaysian Catholic newspaper, was prevented by the Home Ministry from using the word “Allah,” even though it is also the usual word for “God” in the Malay language. Challenging the ruling, the Church brought the case to the High Court in the capital (Kuala Lumpur) and won in December 2009 after the court overturned the ban and upheld the church’s constitutional rights.

The victory, however, didn’t last. The court’s decision was reversed when the Court of Appeal ruled last October that the use of the word “Allah” was “not an integral part of the faith in Christianity.” According to the chief judge on the panel, the ban on the word was legitimized by the apparent susceptibility of Muslims to the conversion efforts of other religions. In response to the ruling, the editor of the Herald maintained that he would appeal again. Catholic churches in Selangor would also continue to use the word “Allah” in their weekend services in Malay, which are mainly attended by parishioners from the neighbouring states of Sabah and Sarawak.

Besides indicating the perpetuation of legal disputes, the tussle doesn’t bode well for interfaith relations in the Muslim-majority country. Ties between Muslims and non-Muslims have already been inflamed. After the 2009 High Court ruling, there was a spate of attacks on churches and other non-Muslim places of worship like Sikh temples. In January this year, two home-made petrol bombs were hurled at a church in the state of Penang. This attack is widely believed to be associated to banners, hung outside three Penang churches, which contained the word “Allah.” Such incidents have worried Malaysian Christians, who compose about nine percent of the country’s population, as well as members of other faiths.

State authorities have been adamant that their increased religious assertiveness is legally justified. The Selangor Islamic Religious Department claims that it was acting under the Selangor Non-Islamic Religions (Control of Propagation Among Muslims) Enactment, a law passed by the state government in 1988 prohibiting all non-Muslims in the state from using 35 Arabic words and phrases, including “Allah,” but also others like “Nabi” (prophet) and “Insya’Allah” (God willing). In a speech in January this year, the Sultan of Kedah, the current head of state of Malaysia, also cited a 1986 ruling by the National Fatwa Council (which issues Islamic edicts) declaring that several words, including “Allah,” were exclusive to Muslims. Christians’ use of such words has been consequently perceived by some conservative Islamic groups as tantamount to a disregard for Muslim sensitivities and a flagrant violation of the law.

Allah, in Arabic, on a medallion hanging in Hagia Sophia, Istanbul – Photo: WikipediaCivil society groups disagree. The Malaysian Consultative Council of Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, Sikhism and Taoism contended that as long as the word “Allah” was not used to proselytize Christianity to Muslims, its use in Christian worship was entirely permissible: any attempts to forbid Christians from using the word would be a violation of Article 11 (4) of the 1957 Federal Constitution (which affirms that federal and state laws can only control or restrict the propagation of any religious doctrine or belief among Muslims).

Allah, in Arabic, on a medallion hanging in Hagia Sophia, Istanbul – Photo: WikipediaCivil society groups disagree. The Malaysian Consultative Council of Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, Sikhism and Taoism contended that as long as the word “Allah” was not used to proselytize Christianity to Muslims, its use in Christian worship was entirely permissible: any attempts to forbid Christians from using the word would be a violation of Article 11 (4) of the 1957 Federal Constitution (which affirms that federal and state laws can only control or restrict the propagation of any religious doctrine or belief among Muslims).

Christians’ use of Bibles containing the word would also be in line with the federal government’s 2011 “ten-point solution,” a series of statements approved by the Malaysian cabinet, which included the declaration that Bibles in all languages (including Malay) can be imported into the country. Constitutional experts interviewed in the local media further argued that state religious enactments like those issued in Selangor, as well as decrees issued by the National Fatwa Council, are not applicable to non-Muslims in the first place, given that non-Muslims in Malaysia cannot be charged in an Islamic court.

The controversy over the word “Allah,” then, can be seen for what it is — a drawn-out process of legal and political contestation closely linked to issues of power and authority, couched in terms of control over language. In effect, to control the use of religious terminology is to impose a linguistic and cultural hegemony that threatens to marginalize minority faith groups. By insisting on the exclusivity of the word “Allah,” state authorities have restricted the discursive environment available for individuals to recognize shared concepts essential for facilitating a bridging of the religious divide.

Muslim intellectuals have been astute in pointing out this danger. Mohamed Imran Mohamed Taib, a founding member of Leftwrite Center, a dialogue initiative for young professionals, made this case during a forum organized by the Center in Singapore early this year: the idea of an “Islam under siege” is a myth, generated through extensive socio-historical and political processes. This is especially the case when race and religion are inextricably intertwined. “In Malaysia,” Imran said, “the idea of Malay supremacy is endemic, and this Malayness is defined exclusively by Islam.” Relating the situation in Malaysia to the ideas of the late Muslim thinker Mohamed Arkoun, Imran explained that the state’s tight control of discursive space had led to a transformation of the “thinkable” (such as the concept of religious freedom and Islam’s shared Semitic roots) into what Arkoun described as the “unthought,” a field of the unthinkable that can expand over time and lead to the diminishment of reason.

Imran argued that the formation of the “unthought” could be similarly observed in Malaysian Islam, leading to an inability to realize, as he states, “the fact that the word “Allah” has and can be used by the Christians (who belong to the same Abrahamic tradition – the “People of the Book”) to refer to the same Ultimate Reality – a universal, and the only One God that both religions preached.”

Forum on ‘Perspectives on Faiths in Society’ in Singapore – Photo: Leftwrite CenterAgreement with Imran comes from Muslim scholars outside the region. Muhammad Musri, president of American-Islam and the Islamic Society of Central Florida, wrote in The Huffington Post in January to urge the Malaysian government to grant the use of the word “Allah” to non-Muslims. He questioned whether the ban could be “an attempt by some in the Malaysian government” to deflect “the anger of poor Malay Muslims over the rising prices of fuel and basic commodities.” Observing that the overlapping of cultures and the predominance of Islam in the country had led to the word “Allah” becoming the standard reference to God in Malay, he noted that the word has also been historically used in Urdu, Farsi, Turkish, and in many translations of Hebrew and Christian scriptures. “Allah,” he pointed out, was a name for God “even before the Prophet Muhammad began teaching Islam.” As an imam who has memorized the Qur’an, Musri argued that the Malaysian court’s ban runs contrary to the “core values and spirit” of the Islamic faith.

Forum on ‘Perspectives on Faiths in Society’ in Singapore – Photo: Leftwrite CenterAgreement with Imran comes from Muslim scholars outside the region. Muhammad Musri, president of American-Islam and the Islamic Society of Central Florida, wrote in The Huffington Post in January to urge the Malaysian government to grant the use of the word “Allah” to non-Muslims. He questioned whether the ban could be “an attempt by some in the Malaysian government” to deflect “the anger of poor Malay Muslims over the rising prices of fuel and basic commodities.” Observing that the overlapping of cultures and the predominance of Islam in the country had led to the word “Allah” becoming the standard reference to God in Malay, he noted that the word has also been historically used in Urdu, Farsi, Turkish, and in many translations of Hebrew and Christian scriptures. “Allah,” he pointed out, was a name for God “even before the Prophet Muhammad began teaching Islam.” As an imam who has memorized the Qur’an, Musri argued that the Malaysian court’s ban runs contrary to the “core values and spirit” of the Islamic faith.

Happily, such values of peace and goodwill have undergirded the actions of certain civil society activists in Malaysia. According to local media reports, a group of Muslims turned up at the Church of Our Lady of Lourdes in Klang (Selangor) on a Sunday morning early this year to show their support to Christians. The congregation was pleasantly surprised, having been warned to expect conservative Malay-Muslim demonstrators organizing protests against the church. Instead, they were greeted by members from Sisters in Islam (an Islamic non-governmental organisation that promotes social equality for women and human rights) along with other Muslim civil society activists. The group included social activist Datin Paduka Marina Mahathir, a former Malaysian prime minister’s daughter, who presented a bouquet of flowers to the parish priest, while parishioners cheered and applauded.

Such events mark the beginning of the healing process in Malaysian interreligious relations, though interfaith advocates should nevertheless be prepared to face more opposition. The right-wing Malay Muslim group Perkasa Youth, for instance, strongly criticized Marina Mahathir for showing solidarity with non-Muslims, arguing that she should have defended the exclusive rights of Muslims to use the word “Allah” instead of supporting Christians. In a statement made to local media, the group’s youth chief questioned Marina’s faith and denounced her actions, asking whether she merely intended to create controversy.

Facing such criticism, civil society and interfaith activists clearly have their work cut out for them. For religious harmony, their efforts remain vital in preventing the issue from escalating further. By encouraging dialogue and engagement, interfaith advocates can inspire others to abandon prejudice and hostility in favor of respect and cooperation. If the “Allah” controversy can be resolved, Malaysia will be known as a positive example of interreligious reconciliation, rather than a country which confiscates Bibles.