By Marcus Braybrooke

NEVER AGAIN

This address was given at a Holocaust Memorial Meeting arranged by the Universal Peace Federation at the Houses of Parliament, London, February 4, 2014. Similar Holocaust Memorial days are held around the world on various days. Ed.

* * *

Today we remember all who died in the Holocaust and subsequent acts of genocide. We express our sympathy for those whose loved ones died or whose lives were ruined – all who still bear the scars of such cruelty. But our mere act of remembering is witness to the need not to lose faith – not to lose hope.

We are reminded too of the deadly danger of not treating another person as a human being.

Among the tragic poems written by children at the Tereisenstadt Concentration camp, there are these lines by Alena Synková in her 1997 book I Never Saw Another Butterfly ( p.69):

I’ve met enough people

Seldom a human being …

I must not lose faith

I must not lose hope.

This made me realise again that the path to genocide begins by dehumanising the other, and I seem to have had several reminders of this in recent days. The curator of a museum about the slave trade saying on the radio that to the traders, the slaves were cargo, not human beings. Then reading that the leader of the 9/11 attack told his colleagues to “treat the victims kindly, like animals,” or that Richard Heydrich, who hosted the Wannsee conference, said that ridding Europe of the “bacilli of Jewry” was a service to mankind. Or one of those who took part in the butchery of the Tutsi in Rwanda: “We no longer saw a human being when we turned up a Tutsi in the swamps … They had become people to throw away, so to speak.”

Holocaust Memorial, Berlin – Photo: Wikipedia

I always shiver when I hear a phrase like “You are a waste of space.” Language matters, and I worry that the word “immigrant” or “being on benefits” is becoming a term of abuse.

But in the new book Responses to Terrorism, Brian Rowan warns of the dangers in the words we use in response – the “demonization of the terrorist,” presenting them as“monsters” or “psychopaths.” Such language “strips away any legitimate motivation for the action … Yet when we speak to some of those directly involved in the actions, we find people just like ourselves, but who made different life choices.” This Rowan insists is in no way to condone the atrocities, but as the book makes clear, to respond to terrorism in like manner is to escalate the cycle of violence.

Too often religious people have made similar divisions between “the saved’ and the “damned”; “Dar al-Isla”’ and “Dar al-harb.” They have, as a recent writer puts it, used the creeds as “barbed-wire fences.” And as a Christian I cannot remember the Holocaust without recalling with shame the Christian share of responsibility for the sufferings of the Jewish people – not only in failing to do more in opposing the Nazis but for centuries of anti-Jewish teaching.

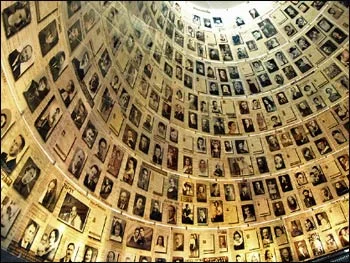

The Yad Vashem Hall of Names in Jerusalem containing pages of testimony commemorating the millions of Jews who were murdered during the Holocaust. – Photo: Wikipedia

Some years ago the then BBC Religious Affairs correspondent Gerald Priestland said that the dramatic change in Christian-Jewish relations in the last fifty years was one of the few items of good religious news that he had reported. Dating back to the Vatican II’s Nostra Aetate, there has been a dramatic change in Christian teaching, which makes clear that the Jews are not to be blamed for the death of Jesus – an accusation that in the past has been a cause of anti-Semitism and teaching that was exploited by the Nazis.

My concern is that too easily priests and congregations – let alone websites – revert to old stereotypes, especially as churches’ annually relive the story of Jesus’ arrest, trial and death. Prejudices are very like weeds. You think you have weeded the garden thoroughly, but then go away for a couple of weeks’ holiday and come back to find the weeds have grown tall again. We need to be constantly vigilant in counter-acting prejudice. Christians, I get the impression, are less interested in relations with Judaism than they were thirty years ago, and criticism of the Israeli government too easily becomes anti-Jewish and anti-Semitic.

Let me then try very briefly to summarise contemporary church teaching. Jesus was a Jew who grew up in a God-fearing home and was a faithful Jew. The disagreements with some Jewish teachers were intra-Jewish debates – probably no less heated than Church of England debates about women bishops. Jesus was popular with the people, and that is why the arrest was made “for fear of the people.” Jesus was put to death by the Roman governor, Pontius Pilate, who was eventually sacked for his cruelty. The Jews as whole were not to blame.

It may be that the high priests wanted Jesus out of the way – the latest version of the internationally famous Oberammergau Passion Play - and indeed the recent TV series “What’s in the Bible” – makes clear that the high priests were in effect puppets of the Romans. The Oberammergau play begins with a scene – not in the Bible – of Pilate summoning the high priest to meet him late at night. Pilate makes very plain that if the priests cannot control the people and stop a riot, he will come and shut down the Temple and take away what little freedom they have. Nicodemus also is given a big part, and takes Jesus’ side and opposes the high priest. There is also a crowd which shout for Jesus’ release – but they are shouted down by those who cry “Crucify.”

In his remarkable book City of Wrong, the Muslim scholar Dr Kamel Hussein says the City of Wrong is Jerusalem, which stands for all humankind. The events of Good Friday illustrate what happens when people sin against their conscience. There is no basis in the Bible for Christians blaming Jews for the death of Jesus – and yet one hears still of playgrounds where Jewish boys are abused as ‘Christ-killers’ and of racism and anti-Semitism on the football pitch.

We need to be constantly aware of the deadly evil of prejudice. All too often the media convey a false picture of Islam, partly by giving unnecessary prominence to the views of extremists which are repudiated by the great majority of faithful Muslims. We think of the prejudice from which Bahai’s suffer in Iran, those countries which still regard homosexuality as a crime, the persecution of new religious movements. As people of faith we need together to speak for and defend all whose human rights are threatened.

Prejudice, which is deliberate ignorance, divides and embitters society. We need to examine our own behaviour and use of language and that of our faith community as well as challenging the prejudices of others. Because prejudice dehumanizes – the other becomes a statistic, an object, a danger, vermin to be destroyed. In Edward Bond’s poem, “How We See,” in Holocaust Poetry (1995), he writes,

After Trblinka

And the spezialkommando

Who tore a child with bare hands

Before its mother in Warsaw

We see differently

We see racist slogans chalked on walls differently

We see walls differently.

After the Holocaust, Do we see differently? The great faiths teach us to see the face of the divine in every human face. Perhaps Holocaust Memorial Day should be a spiritual eye-test – do we see the divine clearly in every human face.

There is an old story about the rabbi who asked his disciples how they knew that night had ended and that day was on its way back. “Could it be,” asked one, “when you can see an animal in the distance and tell whether it is a sheep or a dog?” “No,” replied the rabbi. “Could it be,” asked a second, “when you can look at a tree in the distance, and tell whether it is a fig or an olive tree?” “No,” replied the rabbi. “Well, when is it?” the disciples pressed. “It is when you look on the face of any man or woman and see that he or she is your brother or sister because if you cannot do this, no matter what time it is, the world is still in darkness.”