By Michael Jitosho

A SECOND-GEN'S JOURNEY TO PRIESTHOOD

On April 1, 2004, my world turned upside down. I was rushed from the middle of a normal day at junior high school and immediately brought to the hospital bedside of my father, who had just been diagnosed with terminal cancer. I remember walking into the four-occupant hospital room. The walls glowed with a melancholy yellow stain. I saw his face, which defined the word defeated. As a Japanese immigrant, raising a family of his own in a new country, I cannot imagine how he felt when he received his diagnosis.

He was my role model, mentor, and father and only had a few months to live. I needed to do everything to help him get better and fight his cancer, but deep down I knew everything that could be done had been done. In the many somber nights that followed, leading up to his eventual death, I would lie in bed with fear, insecurity, and pain for my life without my father. However, with the plentiful support from family and friends, I knew it was time for me as the son of my father to become a man and help support my family moving forward.

The Jōdo Shinshū Buddhist Temple in West Covina, California. – Photo: livingdharma.org

At thirteen years of age, I began doing everything around the house that I could – washing dishes, making meals, doing laundry, yard work, helping with shopping, and most of all being a well-behaved son and student for my mom.

Once our family got settled and made our adjustments as a family of three, not four, we needed something more in our lives than simply surviving day by day. So we continued to be active at our local Jōdo Shinshū Buddhist temple in West Covina, California. We attended Sunday services, were involved with Dharma school, helped with fundraisers, and supported the many Japanese American cultural events held by the temple. I did not think much of the Sunday service portion of our temple involvement as a teen, but I always had one ear open and kept listening.

The Youth Group at the West Covina Buddhist Temple on a tour to Okinawa. – Photo: livingdharma.org

Once I entered middle school I advanced from Cub Scout to Boy Scout. This is where I received an opportunity to deeply study the Dharma. While my fellow scouting friends worked on their religious badges for their respective faiths, I sought out the resident minister at my temple to see about earning the Boy Scout Sangha Award. The minister agreed and every Sunday a few hours before the morning service the minister would hold a small-sized class for me, my older sister, working on the equivalent Girl Scout Buddhist award, and another temple member working on his. Together we learned the history of Buddhism, Buddhism 101, as well as rituals which included ringing the bell, chanting, and setting up the altar for services.

After I received my award and was long gone and done with Boy Scouts, I could not help but ask my minister more questions about the Dharma. I wanted more clarity. My questions were not very academic nor were they based on historical text, but I felt the Teachings had a very real and viable element to it and wanted to unveil it. It was quite difficult to understand complex concepts like “other power vs. self power” at that time, but I was never shy about asking questions to deepen my understanding of these more abstract terms.

Understanding Impermanence and Discovering a Vocation

With the passing of my father I experienced the teaching of impermanence. Accepting the idea that life is full of impermanence helped me accept his death. As the years went by I began to realize that the Dharma messages given by the resident minister really resonated with me. I had heard that death defines our existence, and at that point I was beginning to understand what that really meant.

I no longer feared death because I understood death was a natural part of life. Without the fear, I began to look at life differently. My goals for my future quickly changed in high school. Before, when I thought about my career, I considered all the things I needed to buy and have to make myself happy. After my father passed away, those desires slipped away. I realized materialistic wealth and luxuries meant nothing if I were to die tomorrow. I had thought I was surely set on a path for a career in business; but I began to have second thoughts, so I shifted to the health sciences. I was interested in a career focused on improving the lives of people more than making money. Whatever path I ultimately decided to take, I knew I needed to be close to the temple so that I could continue to listen and ask questions.

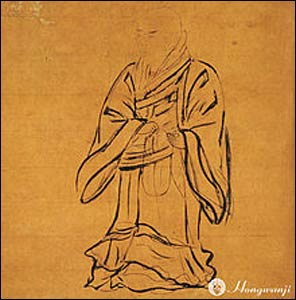

A portrait of Shinran, the founder of the Jōdo Shinshū school of Pure Land Buddhism, located at Nishi Honganji, Kyoto. – Photo: Wikipedia

I began more intensive ritual training under the same resident minister until I eventually got to a point where I was ready to take the first ordination examination as a Buddhist priest. At that point I seriously considered the results of my decision and the responsibility I would have to uphold, should I go through with it. I never thought of myself as being a minister, but the opportunity was before me.

After a nerve-racking chanting examination and an application, I received confirmation that I was eligible to receive my first ordination as a Buddhist priest. While working in Japan, I had the opportunity to make my way to Nishi Honganji, the Jōdo Shinshū mother temple in Kyoto, Japan. There I received my official robes and had my first ordination ceremony.

During one part of the ceremony, which was exclusive to the recipients, all the doors were closed and the electrical lighting was shut off. The only source of light was the candle-light on the altar. The ceremony was done by candle to simulate what it was like to receive ordination during the time of the founder of Jōdo Shinshū Buddhism. As we sat in silence waiting for the ceremony to commence, I reflected on the trek I was about to embark on. It was an experience I will never forget.

I am just beginning to find my role as a young Buddhist priest. Having received first ordination, I do not feel any smarter or any more reverent than anyone. But I see myself as a steadfast student in learning more about the Dharma. To this day I still feel confused – but the more I listen to the Teachings, I continue listening to the Dharma. It is not always easy pursuing the Truth of the Nembutsu. I often ask myself why I am on this path. At times I feel all alone, looking around and seeing few of my peers attending regular Sunday services or religious retreats and events.

Looking back, I ask why I am so persistent about learning the Truth, yet am alone on this quest for the Truth. I pinpoint the moment, the beginning of my spiritual path, to the first day in April, 2004, in that melancholy yellow stained hospital room when I learned about the terminal illness of my hero, friend and father.

Although I was quite young then, I feel very fortunate for what I learned. Encountering my father’s death made me see my entire world differently. My values became about life, about family and relationship with people, and less about things. I was no longer obsessed with having all the luxuries of a secular life like lots of money, owing expensive cars, and buying big houses. That just doesn’t matter anymore. I am on a personal mission to find out why I no longer fear death and why my fervor in finding out the Truth of the Dharma is not so compelling to my peers.