Practical Advice for those Afflicted with Peculiarities in this Area

by John Newton

John Newton (1725-1807)

John Newton, the seagoing slave trader who was converted, became an abolitionist, and wrote “Amazing Grace,” spent the rest of his life as a Puritan pastor, preacher, and poet. His stern theology may startle, even repel some, particularly those whose spiritual life is grounded in silence and listening. Still, his sermon on Christian public prayer is full of interesting advice for those who address God in public, regardless of tradition. Agree or disagree, he raises interesting issues about the personal-eternal relationship in public. Downloaded from Fire and Ice: Puritan and Reformed Sermons. Ed.

John Newton, painted by John Russell, hangs at the Church Mission Society in Oxford.

It is much to be desired, that our hearts might be so affected with a sense of divine things and so closely engaged when we are worshipping God, that it might not be in the power of little circumstances to interrupt and perplex us, and to make us think the service wearisome and the time which we employ in it tedious. But as our infirmities are many and great, and the enemy of our souls is watchful to discompose us, if care is not taken by those who lead in social prayer, the exercise which is approved by the judgment may become a burden and an occasion of sin . . .

Length of Prayers

The chief fault of some good prayers is that they are too long; not that I think we should pray by the clock, and limit ourselves precisely to a certain number of minutes; but it is better of the two, that the hearers should wish the prayer had been longer, than spend half the time in wishing it was over. This is frequently owing to an unnecessary enlargement upon every circumstance that offers, as well as to the repetition of the same things. If we have been copious in pleading for spiritual blessings, it may be best to be brief and summary in the article of intercession for others, or if the frame of our spirits, or the circumstances of affairs, lead us to be more large and particular in laying the cases of others before the Lord respect should be had to this intention in the former part of the prayer.

There are, doubtless, seasons when the Lord is pleased to favour those who pray with a peculiar liberty: they speak because they feel; they have a wrestling spirit and hardly know how to leave off. When this is the case, those who join with them are seldom wearied, though the prayer should be protracted something beyond the usual limits. But I believe it sometimes happens, both in praying and in preaching, that we are apt to spin out our time to the greatest length, when we have in reality the least to say. Long prayers should in general be avoided, especially where several persons are to pray successively; or else even spiritual hearers will be unable to keep up their attention. And here I would just notice an impropriety we sometimes meet with, that when a person gives expectation that he is just going to conclude his prayer, something not thought of in its proper place occurring that instant to his mind, leads him as it were to begin again. But unless it is a matter of singular importance, it would be better omitted for that time.

Preaching in Prayers

The prayers of some good men are more like preaching than praying. They rather express the Lord’s mind to the people, than the desires of the people to the Lord. Indeed this can hardly be called prayer. It might in another place stand for part of a good sermon, but will afford little help to those who desire to pray with their hearts. Prayer should be sententious, and made up of breathings to the Lord, either of confession, petition, or praise. It should be not only Scriptural and evangelical, but experimental, a simple and unstudied expression of the wants and feelings of the soul. It will be so if the heart is lively and affected in the duty, it must be so if the edification of others is the point in view.

Method in Prayer

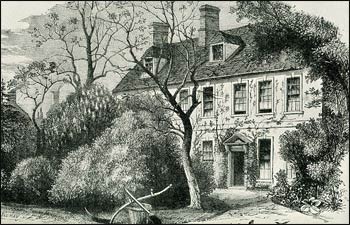

The vicarage in Olney where Newton wrote the hymn “Amazing Grace” – Graphic: Wikipedia

Several books have been written to assist in the gift and exercise of prayer, and many useful hints may be borrowed from them. But a too close attention to the method therein recommended, gives an air of study and formality, and offends against that simplicity which is so essentially necessary to a good prayer, that no degree of acquired abilities can compensate for the want of it. It is possible to learn to pray mechanically, and by rule; but it is hardly possible to do so with acceptance and benefit to others.

When the several parts of invocation, adoration, confession, petition, etc., follow each other in a stated order, the hearer’s mind generally goes before the speaker’s voice, and we can form a tolerable conjecture what is to come next.On this account we often find that unlettered people who have had little or no help from books, or rather have not been fettered by them, can pray with an unction and savour in an unpremeditated way, while the prayers of persons of much superior abilities, perhaps even of ministers themselves, are, though accurate and regular, so dry and starched, then they afford little either of pleasure or profit to spiritual mind. The spirit of prayer is the fruit and token of the Spirit of adoption.

The studied addresses with which some approach the throne of grace remind us of a stranger’s coming to a great man’s door; he knocks and waits, sends in his name, and goes through a course of ceremony, before he gains admittance, while a child of the family uses no ceremony at all, but enters freely when he pleases, because he knows he is at home. It is true, we ought always to draw near the Lord with great humiliation of spirit, and a sense of our unworthiness. But this spirit is not always best expressed or promoted by a pompous enumeration of the names and titles of the God with whom we have to do, or by fixing in our minds beforehand the exact order in which we propose to arrange the several parts of our prayer. Some attention to method may be proper, for the prevention of repetitions; and plain people may be a little defective in it sometimes; but this defect will not be half so tiresome and disagreeable as a studied and artificial exactness.

Peculiarities of Manner

Many – perhaps most – people who pray in public have some favourite word or expression which recurs too often in their prayers, and is frequently used as a mere expletive, having no necessary connection with the sense of what they are speaking. The most disagreeable of these is when the name of the blessed God, with the addition perhaps of one or more epithets, as Great, Glorious, Holy, Almighty, etc., is introduced so often and without necessity, as seems neither to indicate a due reverence in the person who uses It, nor suited to excite reverence in those who hear. I will not say that this is taking the Name of God in vain, in the usual sense of the phrase: it is, however, a great impropriety, and should be guarded against. It would be well if they who use redundant expressions had a friend to give them a caution so that they might with a little care be retrenched; and hardly any person can be sensible of the little peculiarities he may inadvertently adopt, unless he is told of them.

There are several things likewise respecting the voice and manner of prayer, which a person may with due care correct in himself, and which, if generally corrected, would make meetings for prayer more pleasant than sometimes they are. . . Very loud speaking is a fault, when the size of the place and the number of the hearers do not render it necessary. The end of speaking (in public) is to be heard: and when that end is attained a greater elevation of the voice is frequency hurtful to the speaker, and is more likely to confuse a hearer than fix his attention. I do not deny but allowance must be made for constitution, and the warmth of the passions, which dispose some persons to speak louder than others. Yet such will do well to restrain themselves as much as they can. It may seem indeed to indicate great earnestness, and that the heart is much affected; yet it is often but false fire. It may be thought speaking ‘with power,’ but a person who is favoured with the Lord’s presence may pray with power in a moderate voice; and there may be very little of the power of the Spirit, though the voice should be heard in the street and neighbourhood.

The other extreme of speaking too low is not so frequent; but, if we are not heard, we might as well altogether hold our peace. It exhausts the spirits and wearies the attention, to be listening for any length of time to a very low voice. Some words or sentences will be lost, which will render what is heard less intelligible and agreeable. If the speaker can be heard by the person furthest distant from him, the rest will hear of course.

The tone of the voice is likewise to be regarded. Some have a tone in prayer so very different from their usual way of speaking, that their nearest friends, if not accustomed to them, could hardly know them by their voice. Sometimes the tone is changed, perhaps more than once, so that if our eyes did not give us more certain information than our ears, we might think two or three persons had been speaking by turns. It is a pity that when we approve what is spoken we should be so easily disconcerted by an awkwardness of delivery: yet so it often is, and probably so it will be, in the present weak and imperfect state of human nature. It is more to be lamented than wondered at, that sincere Christians are sometimes forced to confess: ‘He is a good man, and his prayers as to their substance are spiritual and judicious, but there is something so displeasing in his manner that I am always uneasy when I hear him’.

Informality in Prayer

Contrary to this, and still more offensive, is a custom that some have of talking to the Lord in prayer. It is their natural voice indeed, but it is that expression of it which they use upon the most familiar and trivial occasions. The human voice is capable of so many inflections and variations, that it can adapt itself to the different sensations of the mind, as joy, sorrow, fear, desire, etc. If a man was pleading for his life, or expressing his thanks to the king for a pardon, common sense and decency would teach him a suitableness of manner; and anyone who could not understand his language might know by the sound of his words that he was not making a bargain or telling a story.

How much more, when we speak to the King of kings, should the consideration of his glory and our own vileness, and of the important concerns we are engaged in before him, impress us with an air of seriousness and reverence, and prevent us from speaking to him as if he was altogether such an one as ourselves! The liberty to which we are called by the gospel does not at all encourage such a pertness and familiarity as would be unbecoming to use towards a fellow-worm, who was a little advanced above us in worldly dignity.

I shall be glad if these hints may be of any service to those who desire to worship God in spirit and in truth, and who wish that whatever has a tendency to damp the spirit of devotion, either in themselves or in others, might be avoided.