By Benjamin DeVan

Comparative Theology

Does theology have a role in discussions of spiritual discernment, meaning-making, and concerns about syncretism in contemporary interfaith worlds and culture? Should theologians and theologically interested believers limit themselves to developing and deepening the knowledge of their own tradition, or is there value engaging theologies beyond one’s chosen faith or worldview? Are these endeavors mostly or finally mutually exclusive?

Francis Clooney, the director the Center for World religions at Harvard, envisions “Comparative Theology” as going beyond comparing different theologies to utilizing resources of other traditions to better articulate and understand one’s own. Or, to borrow from Proverbs 27:17, as “iron sharpens iron,” so can one religious tradition sharpen another.

Photo: Patheos

But is such sharpening valuable? And is Comparative Theology viable as a bridge, sub-specialty, or third discipline employing other religious traditions to refine one’s own? By consulting disparate doctrines can we filter gold from theological dross? Can we evaluate, incorporate, synthesize, and organize insights from multiple religions while attempting, in John Cobb’s words, to do “justice to the basic commitments of all”?

As a former and future religion/humanities university instructor, I am regularly adjured by the inquisitive and incredulous as to why anyone, especially students grudgingly registered to meet a curriculum requirement, should even bother studying religion or theology at all...

First, I point out that it is impossible to do justice to any major religious tradition simply by taking a course, reading a book, declaring a major, enrolling in seminary, or earning a Ph.D. Any of these may supply fertilizer for lifelong rumination, but numerous volumes are published explicating thousands of theological themes barely mentioned, let alone surveyed, in most college, university, or seminary modules and seminars. Nevertheless, completing an undergraduate class or sifting through theological tomes yields a sampler taste of the greater feast within the study of religion, a banquet enhanced by a useful menu, talented academic chefs, and the desire to cultivate an astute sense of taste.

Second, religion is difficult to define. Wilfred Cantwell Smith doubts “religion” is a valid category for describing non-European beliefs, rituals, and values, since it is a term originating in Europe and applied, Smith avows, haphazardly to non-European cultures and contexts. Buddhist feminist Rita Gross is more optimistic about quantifying religion but cautions, “Everyone has an intuitive sense of what is meant by the concept of religion, but these definitions are often limited by ethnocentrism. They often assume... all religions are... like religion in one’s own culture.”

Religion has been classified as the voice of deepest human experience, behaviors concerned with supernatural beings and forces, the longing for or encounter with the transcendent numinous, a feeling of absolute dependence, a taste for the infinite, and the chief fact regarding a person’s practical beliefs about, “vital relations to the mysterious universe, and . . . duty and destiny there” (Thomas Carlyle). The Dalai Lama suggests all the major religions are “dedicated to the achievement of permanent human happiness.” Gandhi believed, “In reality, there are as many religions as there are individuals.” G.K. Chesterton, later echoed more famously by Paul Tillich, wrote that religion is one’s sense of “ultimate reality,” of whatever meaning someone finds in his or her own existence, or the existence of anything else.

A concurrent controversy is what counts as religion and what does not. Is Atheism the religious belief that there is no God? What about political philosophies like Communism, where humankind or the state is ultimate? Are sports with fervent rituals, rules, loyalties, and “idols,” religions? Comparative Theology clarifies such queries by investigating religion’s multivalent manifestations and inspecting the potentially theological nature of ideas and actions that less attentive onlookers or participants compartmentalize as secular or irrelevant to religion.

Third, because religion eludes easy definition, its boundaries are notoriously ambiguous and porous, interweaving issues from anthropology, archaeology, the arts, cosmology, ethics, history, literature, philosophy, politics, psychology, sociology, and even theoretical physics. According to Christopher Dawson, “The great religions are the foundations on which the great civilizations rest.” Thus, Comparative Theology equips us to appreciate richness in history and culture we might otherwise miss. From the poetry of John Donne to the majesty of the Taj Mahal, to the intricacies of Indian dance:

One cannot study themes of art or forms of architecture without some reference to the impetus provided by religion . . . one cannot learn about music and poetry without somehow noting the influence of religious inspiration. History, sociology, and anthropology cannot be taught or interpreted without consideration of religious customs and practices . . . psychology without reference to religion as a force that motivates, regulates, influences, and even directs . . . behavior . . . is almost impossible. (S.A. Nigosian)

Comparative Theology in this sense is worthwhile even for atheists, since it does not automatically endorse theologies it compares any more than researching racism makes one racist, or taking art history necessitates daubing paint to canvas ourselves. Will Deming elaborates:

For the religious, the study of religion can give one a deeper appreciation for his or her own religious tradition . . . It also enables a person to articulate his or her tradition better to others, either to edify one’s own group or for purposes of evangelism or interfaith dialogue. For both the religious and the nonreligious – the atheist, the agnostic, or the comfortably uninterested – an appreciation of religion gives one insight into dealing with religious people of all sorts.

Gary Kessler recognizes religion as “a force that influences for good or for ill, the lives of practically everyone who is alive. So much of human history and culture remains a mystery if we cannot comprehend the role religion has played and continues to play in the development of human institutions, values, and behavior.” For example, “American culture . . . cannot be fully understood without knowing something about the role that Christianity played in shaping its political, judicial, and educational institutions, not to mention . . . individual freedom and human rights . . . religious ideas were used to promote the destruction of indigenous peoples and to end it, to promote slavery and to stop it.”

Karen Farrington likewise extols, “In his darkest hour it has taken more than food and water to sustain benighted man. Religion has been his comforter, his prop, his reason for existing.” Comparative Theology strives to ascertain why, in what way, and to what end.

Fourth, while it has been said one ought not to talk politics, sex, or religion in polite society, Comparative Theology concerns politics, sex, andreligion! Studying themes that matter intensely is enlightening and invigorating, yet it can evoke strong emotions by touching on topics intensely personal.

Unlike some professors, I decline to be a faith-terminator who “shoots to kill” at students’ religious beliefs. Most students have few tools and limited time to winnow wheat from chaff flung by hostile, heavily armed authority figures. I hope religious and secular students alike find their preconceptions challenged by religious and theological inquiry (cf. James 1:2-5), but while spiritual depth is a worthy goal for Comparative Theology, spiritual death is not. In the words of Alex Shand and (purportedly) Cardinal John Henry Newman, universities and Comparative Theology within and beyond ought to be where, “mind clashes with mind, and sparks of brilliant intelligence are set flying, as from the sharp contact of flint striking upon steel.” Or, to use two complimentary metaphors, Comparative Theology ought to serve as a womb for nurturing seeds of creativity and a marketplace to confront, analyze, and ultimately accept or reject ideas.

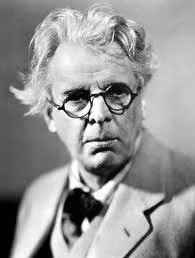

W. B. Yeats

Francis Clooney contends, “If we choose to remain in our original tradition, remaining is now a real choice made in light of real alternatives.” Even so, such variables must be balanced with vulnerability inherent to subjecting personal beliefs to scrutiny and mutually seeing ourselves as others see us. As W.B. Yeats poeticized:

Had I the heavens’ embroidered cloths,

Enwrought with golden and silver light,

The blue and the dim and the dark cloths

Of night and light and the half-light,

I would spread the cloths under your feet:

But I, being poor, have only my dreams;’

I have spread my dreams under your feet;

Tread softly because you tread on my dreams.

A longer version of this article, including footnotes and references and titled “As Iron Sharpens Iron, So Does One Religious Tradition Sharpen Another,” was published March 2010 in the Journal of Comparative Theology.