By Marcus Braybrooke

REMEMBERING THE INTERFAITH MOVEMENT – ENVISIONING AN INTERFAITH MOVEMENT

The recent Parliament of World Religions in Salt Lake City has been called the “123rd birthday of the international interfaith movement,” which is often said to have had its origin at the Chicago Parliament in 1893. It was a time to celebrate the global growth of the movement and its growing maturity. The emphasis was no longer on the need to talk to each other but on what we should be doing together.

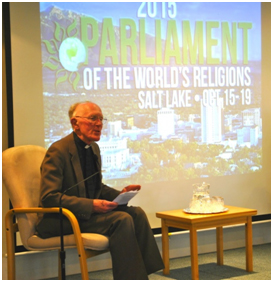

Marcus Braybrooke speaking at a pre-Parliament workshop about the theme of this year’s Parliament of the World’s Religions, “Reclaim the Heart of Our Humanity”. – Photo: Parliament of the World’s Religions

The overall theme was the urgent need to “Reclaim the Heart of Our Humanity.” This was translated into the action we and our faith communities should be taking on climate change, hate crime and violence, women’s rights, the rights of indigenous peoples, emerging leadership, and the widening wealth gap. As the Dalai Lama said in his message, “Action, not just words is needed.”

Yet, with so much for which to be thankful, I have been asking myself – especially in the shadow of the recent massacres, reports of religious hatred, and pictures of the plight of refugees – “What have we achieved?”

In reflecting on the Parliament I wish that it had been more multi-disciplinary as well as multi-faith. It renewed my wish, that while there is increasing cooperation between faith communities and the UN, that there be a Spiritual Advisory Council at the UN, which the World Congress of Faiths has long advocated. But until that happens, could we not set up working parties to examine the practicalities of key issues? Yes, there are lots of specialist agencies, but are faith leaders talking to them? They of course are too busy, but they need to appoint specialists ready to tackle hard questions and report on them.

Concerns about an Interfaith Movement

Those who are critical of the interfaith movement suspect that the real intention is covertly to spread Christian or Western values. It is true that much of the initiative for interfaith dialogue has come from Christians, and there is still debate in the churches whether dialogue is a form of mission. Moreover, most of the major international interfaith organisations, whose work I greatly admire, are based in the U.S. Complicating everything is the persistent suggestion that the real intention of interfaith is to create a new one-world religion.

Perhaps the key question is – How do you read scripture? One may believe that scripture is the very word of God; but however unchanging, interpretation changes because we live in different centuries. Any passage needs to be read in context and in the light of the overall teaching of a religion. One Muslim described the Qur’an as “love letters from God.” If you are old enough, think back to love letters that you wrote (now it would be a text). Suppose in writing to your beloved, you put “I can wait to see you” instead of “I cannot wait to see you.” You would hope that she realised it was a mistake and that the romance was not cooling off. I was taught that we should read the Bible “with the mind of Christ.” One school of shariah says that where there is doubt about interpretation you should always choose the most humane and merciful.

My bigger concern is that the criticisms of the interfaith movement may make its practioners defensive. At the Melbourne Parliament of World Religions in 2009, the catch-phrase was “Respect for the Other.” Now that, of course, is welcome. We need to live with those whose views and beliefs are different. But this seems to me to sidestep the search for truth and greater unity. I know that you may ask, with Pilate, “What is truth?” We never attain it; but like the research scientist, the theologian hopes to deepen our knowledge and understanding.

It is, of course, vital that people of all faiths act together to seek peace to defend human rights, to help the poor and the marginalised, and to protect the environment. It is right that a lot of our energy should go into this. It should be a priority. Yet we can act together and become friends whilst still maintaining the finality of our faith.

Remembering the Heart of the Matter

But this has left the critics unanswered. We need to look back to some of the pioneers of the interfaith movement who were inspired by a mystical experience. The pioneers of interfaith certainly hoped it would issue in practical benefits of reinforcing shared moral values and promoting peace. Yet this would arise, they thought, from a new awareness of the underlying unity of all life. It was not just a matter of learning about other religions: it was also learning from them – what Jacques-Albert Cuttat, Swiss ambassador to India in the 1960s, called a “meeting in the cave of the heart.”

The word mysticism can be misleading. It has been said that ‘mysticism’ begins in mist and ends in schism. The physicist Stephen Hawking said mysticism is for those who can’t do maths. George Cairns replied, “Mystics are people who don’t need to do maths. They have direct experience.”

Sufi Ibn ‘Arabi (1165-1240 CE) – Photo: Wikimedia

The importance of the mystics’ witness is that there is a unity or oneness beyond our particular path. Quite often when you go to see the family, someone will ask “what sort of journey did you have?” You may have been delayed every step of the way, but once you are all together the delays don’t matter. In the same way, when we are overwhelmed by the love of God, how we got there pales into insignificance. Jesus said to the woman of Samaria, “The day is coming when you will worship the Father neither on this mountain, nor in Jerusalem … A time is coming when true worshippers will worship the Father in spirit and in truth.”

The Sufi Ibn ‘Arabi spent much of his life praying the traditional prayers of a Muslim but came to see that to have lived one religion fully is to have lived them all. It was at the heart of the revealed forms of religion that he found the formless and the Universal, as he wrote in these beautiful words:

My heart has become capable of every form:

it is a pasture for gazelles and a convent for Christian monks,

A temple for idols and the pilgrims’ Ka’ba and the tables of the Torah,

and the book of the Qur’an.

I follow the religion of Love:

Whatever way Love’scamels take, that is my religion and my faith.

The poet Rumi said,

The religion of love is apart from all religions:

For lovers (the only) religion and creed is God.

Not Christian or Jew or Muslim

Not Hindu, Buddhist, Sufi or Zen

Not any religion or cultural system.

I am not from the east or the west …

I belong to the beloved

And have seen the two worlds as one.

I could give many more examples; but a final point – if we have had even a glimpse of this reality, then we begin to reflect in our lives something of the boundless love of God and realise as Desmond Tutu said, ‘There is nothing that cannot be forgiven and there is no one who is beyond forgiveness.”