No Longer Hidden

Teaching the Divine Feminine

By Vicki Garlock

This 1750 manuscript, called the Esther Scroll or megilla, tells Queen Esther’s story as recorded in Jewish and Christian scripture. – Photo: Wikipedia, public domain

The recent celebration of Purim – one of the most entertaining holy days in Jewish culture – provides an opportunity to reflect on the ever-present, but somewhat elusive nature of the divine feminine. Queen Esther, the heroine of Purim, is never described in terms of divinity, but her role in the miraculous deliverance of her people give Jews young and old an annual festival to honor women leaders with readings of the Esther story, gifts of food, acts of charity, and a great feast – it’s a very teachable tale!

During my years of interfaith work, however, I have heard accusations of overbearing patriarchy leveled at nearly every major faith tradition. Frankly, there’s solid evidence to support the claims. The divine feminine is often veiled to the point of total banishment. Only a small minority of religions remain blameless. But if you seek her out in the world’s religions, you’ll find the divine feminine very much does exist. Like the women of the Democratic party who increased their visibility by wearing white to Donald Trump’s Feb. 28 address to Congress, the light of the divine feminine is hiding in plain sight, waiting to be lifted up and illuminated.

Teaching the divine feminine to kids requires both effort and ingenuity. The myths and legends are there; the child-friendly packets are not. So interfaith teachers need to get in gear. Instead of bemoaning the fact that yet another generation of young adults remains unfamiliar with herstory, we need to move our attention front and center to the divine feminine. We need to buck prevailing tends and do so when kids are young. Developmental research shows that by the age of three, kids begin to self-identify as a boy or a girl and start labeling toys as being most appropriate for males or females. Boy-girl categorization structures are among the first schemas to develop in children, and by the age of five, kids are using those categories to develop gender scripts that cluster and categorize all manner of behaviors. Waiting until the teenage years or later to teach about the divine feminine means we miss an early, age-appropriate window of opportunity.

Teaching the usual faith-based narratives results, almost automatically, in a male-centric view of the divine. If we want to change that, we need to start with the stories. Here are some ideas to get you started. Citations and website URLs can be found at the end.

Women of Creation

Kids have a lot to say about how the world came to be. Just ask them. Ask how the stars ended up in the sky, why the oceans move, or how fish got their fins. You’ll be amazed by the depth and breadth of their ideas. In the Abrahamic traditions, all those things are attributed to a God who is male, so you can start by replacing all those instances of “he” and “his” with a more gender-neutral world. But you can also take the next step and share stories of creator-women who are integral to the world as we know it.

Rangi and Papa, world-parents in the Maori creation story – Photo: Wikimedia, Kahuroa

In Native American traditions, there is the Grandmother who gave her life so the people could have corn and Grandmother Spider who stole the sun so the people could have light and warmth. From Chinese culture, we have the goddess, Nuwa, who created people from the dust of the earth. And there is Mother Earth – Pachamama to the Incans, Gaia to the Greeks, and Terra to the Romans – who is the keeper/giver of life, fertility, power, and wisdom.

There are also beautiful “world-parent” myths where creation emerges from a man and a woman. One of my favorites is the Maori myth of Rangi (male) and Papa (female). Another fun one is the ancient Egyptian tale of Shu (male) and Tefnut (female), Ra’s offspring, and their children, Geb (male) and Nut (female). Sometimes, the feminine energy becomes the Earth; sometimes, she becomes the Sky. Either way, these stories show the inextricable link between the masculine and feminine and the important role women play in making the world complete.

In addition to the Female Creator motif, we also find the divine feminine in specific aspects of nature – in the heavens, in plants, and in the changing seasons. She is fire and water. She is birth and death. She is peace and war. In ancient, polytheistic, Earth-based traditions, her pervasiveness can become overwhelming to newcomers. Don’t let that dissuade you – all sorts of riches await you.

From the East

Shri Lakshmi is one of Hinduism’s most loved deities. – Photo: Wikimedia, Bazar Art

Eastern traditions such as Hinduism, Taoism, and Buddhism offer a slightly more manageable pantheon. Like the world-parent myths, the Taoists emphasize Yin and Yang – the interconnected and interdependent nature of the One, the Tao. Yin is the cosmic feminine. This complementary, male-female nature of the universe is mirrored in the Hindu stories of Shakti (feminine) and Shiva (masculine); Saraswati (feminine) and Brahma (masculine); Lakshmi (feminine) and Vishnu (masculine); and their avatars, Radha (feminine) and Krishna (masculine); and Sita (feminine) and Rama (masculine).

A few notable stand-alone feminine deities also come to us from the East. Durga is probably the most well-known devi from the Hindu tradition. She and her various aspects are honored in the fall during the days of Navratri. Avalokitesvara, goddess of compassion, is probably the best known deity from the Buddhist tradition. Although sometimes venerated as male, her divine energy is usually portrayed as female in China (Kwan Yin) and Japan (Kannon).

Abrahamic Traditions

In the Abrahamic traditions, the emergence of monotheism resulted in the near-total disappearance of the divine feminine. However, the Hebrew and Christian Bibles and the Muslim Qur’an and Hadith contain numerous stories of exemplary women worth emulating. In Hebrew scripture, we find:

- Deborah: prophetess and sole female judge of pre-monarchic Israel,

- Miriam: prophetess and sister to Moses and Aaron,

- Ruth: model of loving kindness and familial loyalty, and

- Esther: Queen to King Ahasueras, savior of the Jewish people, and Purim honoree.

In the Christian New Testament, we also find Mary, the mother of Jesus, and Mary Magdalene.

A mosaic of the Virgin Mary and Jesus from the Hagia Sophia cathedral in Istambul (c. 1118 CE) – Photo: Wikimedia, Josep Renalias, Cc.3.0

The Qu’ran has its own list of prominent women. Maryam (Mary), the mother of Isa (Jesus), gets more Muslim attention than we find in the Christian text. She is the only woman identified by name in the Qur’an and is given her own chapter (Surah 19). The Pharaoh’s wife, Asiyah, who adopted Moses as her son, is honored as an admirable and virtuous woman. Eve also holds an interesting role. Although not named in the Qur’an, she is named in later writings as Hawwa (which closely matches her Hebrew name, Hawwah). She is also portrayed as Adam’s equal, both as the progenitor of humankind and as his partner in eating the forbidden fruit.

Zulaykha, wife of Yusuf’s (Joseph’s, in English) master when Yusuf was enslaved in Egypt, is another significant female figure in Muslim culture. Her tale is sprinkled throughout Surah 12 of the Qur’an, titled Yusuf. Hagar, the handmaid of Sarah, who bore Abraham’s son, Ishmael, is also extremely important. Even though she is never mentioned by name in the Qur’an, her son, Ishmael, is widely recognized in the Islamic tradition as the child Abraham was asked to sacrifice and as the ancestor of the Prophet Muhammad.

So how does one begin to share the divine feminine with kids?

Start with Something that Speaks to You

There is no perfect starting point, especially since the divine feminine has been neglected for so long. So, start with your favorites. Are you enthralled by volcanoes? Start with the legends of Pele, the Hawaiian volcano goddess. Do you love flowers? Read the Australian aboriginal tales of Krubi, who gave the people the mountain which rose upon her death, or Myee, the beautiful moth, who shed her colors to dye the desert blooms. Have you found a good moon craft? Share the story of Chang’e, the Chinese moon goddess whose story of flight is told during mid-autumn moon festivals.

Don’t Overthink the Details

Then jump in. The divine feminine is ancient and pervasive, and her tales have morphed repeatedly with time. Every legend will have variations. Don’t let anxiety prevent you from sharing her essence. Don’t let your perceived lack of knowledge hinder your attempts to bring the divine feminine out of darkness and into the light.

Her time has arrived. It’s time to share her power.

References

Single-Story Books

Deborah (Bible Stories Mig&Meg Book 10) by Adriano Pinheiro. Amazon Digital Services, 2015.

Earth Mother by Ellen Jackson (author), Diane Dillon (illus.), and Leo Dillon (illus.). Walker Childrens, 2005.

Nuwa Creating Human Beings (Illustrated Famous Chinese Myths Series) by Shen Hong (author) and Duan Lixin (illus.). China Intercontinental Press, 2013.

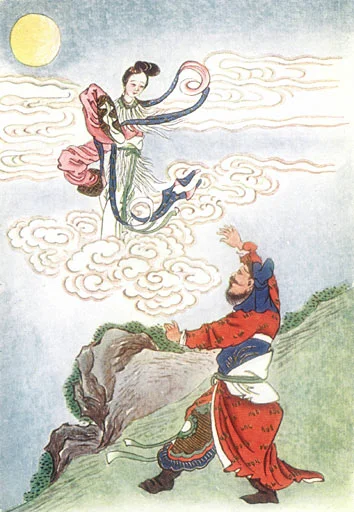

Chang’e, Chinese Moon goddess, flies to the moon – Photo: Wikimedia, E.T.C Werner

Story of Esther: A Purim Tale by Eric A. Kimmel (author) and Jill Weber (illus.). Holiday House, 2011.

Collections Containing Divine Feminine/Goddess Stories

Circle Round by Starhawk and Diane Baker. Bantam, 2000.

Creation: Read-Aloud Stories from Many Lands by Ann Pilling (author) and Michael Foreman (illus.). Candlewick Press, 1997.

Keepers of the Earth: Native American Stories and Environmental Activities for Children by Michael J. Caduto and Joseph Bruchac. Fulcrum Publishing, 1997.

Stories from the Billabong by James Vance Marshall and Francis Firebrace. Francis Lincoln Children’s Books, 2008.

Storyteller’s Goddess: Tales of the Goddess and Her Wisdom from Around the World by Carolyn McVickar Edwards. HarperSanFrancisco, 1991.

Tales of Hindu Gods and Goddesses by Divya Jain (author) and Ajay Kumar (illus.). Unicorn Books, 2010.

Selected Web Sites