On These Shoulders

by Jeffery D. Long

Although no single person, group of persons, or religious tradition can be solely credited with the emergence of the interfaith movement – a vast and complex movement to which many hands and minds have contributed – it is certainly true that the interfaith movement as it exists today would be inconceivable without the contributions of Sri Ramakrishna and Swami Vivekananda.

Sri Ramakrishna Paramahamsa – Photo: Wikipedia

Sri Ramakrishna Paramahamsa (1836-1886) was a Hindu sage and mystic whose vivid and powerful visions of divinity transcended religious boundaries. He was born and reared in a poor Brahminfamily in Kamarpukur, a village in rural Bengal in the eastern part of India. Ramakrishna was predisposed from childhood to profound states of spiritual absorption, or Samadhi. Skeptics as early as his contemporary, William James – and even some in Ramakrishna’s immediate milieu who knew him directly – have speculated about the possibility that he suffered from some kind of neurological disorder. For Ramakrishna, though, if his experiences were indeed side effects of a disorder, it was a blessed and welcome one; his experiences took him to the heights of ecstasy and gifted him with insight and wisdom that attracted legions of followers.

Ramakrishna’s altered states of consciousness were often induced by music or spiritual conversation. Sometimes, though, they were evoked by the sight of natural beauty, such as his first recorded Samadhi as a small boy when he was overwhelmed by the sight of white geese flying against the background of a dark storm cloud. A few years laterhe entered Samadhi publicly on stage in front of his entire village while playing the role of the Hindu deity Shiva. Many in the audience were alarmed and concerned for the boy’s physical and mental health. For others, however, it was as if he had indeed become Shiva, completely absorbed in a divine state of consciousness.

When Ramakrishna was nineteen years old his elder brother, Ramkumar, became the priest at the temple of the Goddess Kali in Dakshineshwar, near Kolkata. Ramakrishna replaced Ramkumar in this role the following year due to Ramkumar’s illness and tragic, premature death.

Kali, the Mother Goddess, is at once fascinating and terrifying, bringing to mind Rudolf Otto’s famous definition of the Sacred as the mysterium tremendum et fascinans. She is at once the compassionate protector all beings, Her children, and the slayer of the demonic in each person – selfishness, arrogance, and ignorance. She is represented as a demon-slayer holding the severed head of a demon She has decapitated and wearing a garland and a girdle of severed demonic heads and limbs. Her protruding tongue is blood red since the particular demon she is depicted as fighting – the Raktabija, or “blood-seed” – has the ability to regenerate himself with each drop of his blood that touches the earth. Kali stands on the body of her husband, Shiva, the divine consciousness who is at all times aware of and observing Her dance of life and death – the cosmic process of death and rebirth over which She presides.

The Goddess Kali in a Kolkata Temple – Photo: Wikipedia

Although deeply devout, Ramakrishna was no stranger to skeptical thought. He felt that if he was to serve as the priest of this Goddess, he should not do his duties merely mechanically, but always with the vision of the living Kali in mind. He wanted to know Her in a direct, vivid way, like the sages and saints of old, to know that he was not just waiting upon a cold, dead image made of stone but serving a living Goddess.

He became filled with an overpowering desire – some might say even an obsession – with receiving the true vision, the Darshan, of the Divine Mother. In his words, “I felt as if my heart were being squeezed like a wet towel. I was overpowered with a great restlessness and a fear that it might not be my lot to realize Her in this life. I could not bear the separation from Her any longer. Life seemed to be not worth living. Suddenly my glance fell on the sword that was kept in the Mother’s temple. I determined to put an end to my life. When I jumped up like a madman and seized it, suddenly the blessed Mother revealed Herself.

“The buildings with their different parts, the temple, and everything else vanished from my sight, leaving no trace whatsoever, and in their stead I saw a limitless, infinite, effulgent Ocean of Consciousness. As far as the eye could see, the shining billows were madly rushing at me from all sides with a terrific noise to swallow me up! I was panting for breath. I was caught in the rush and collapsed, unconscious. What was happening in the outside world I did not know; but within me there was a steady flow of undiluted bliss, altogether new, and I felt the presence of the Divine Mother.” (From The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, translated by Swami Nikhilananda in 1942, pp. 13-14.)

Ramakrishna’s appetite for such vivid, direct experiences of the forms of the Divine was voracious. He remained until his last day on earth a devotee of Kali, whose name he called with his dying breath. However, he became equally determined to experience divinity in as many forms as he possibly could. With as much devotion as he had in his quest for the vision of the Divine Mother, he dedicated himself, in turn, to worship of each of main deities of Hinduism and had vivid, direct experiences of Shiva, Rama, Krishna, and under the guidance of a monk of the Advaita Vedanta tradition, of the impersonal absolute beyond any particular form – Nirguna Brahman.

Having experienced divinity in the personal and impersonal modes offered by Hindu traditions, Ramakrishna then practiced, in turn, Islam and Christianity. It is certainly possible to raise skeptical questions about his practices within these two traditions; he did not, for example, seek baptism or attend church services, but rather listened to readings from the Bible in the home of a friend. He was nevertheless led to profound visionary experiences of the Prophet Muhammad and of Christ and went into Samadhi at the sight of a painting of the Madonna and Child. In Ramakrishna’s judgment and that of the tradition that subsequently emerged in his name, he had experientially proven what came to be his central teaching: Yato mat, tato path. Each religious tradition is a valid path to the same ultimate destination: the direct, experiential realization of divinity.

Ramakrishna’s experiences transformed his character profoundly and attracted many followers from all walks of Bengali society throughout the latter years of his life. He finally succumbed to throat cancer in August of 1886.

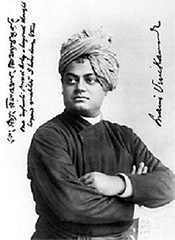

Swami Vivekananda in a photo taken in Chicago in 1893 – Photo: Wikipedia

One of Ramakrishna's followers was a young skeptic named Narendranath Datta, or Naren, as he was then known to his friends. Young Naren’s background could not have been more different from that of Ramakrishna. The English-educated son of an attorney, Naren was born to the Kolkata intelligentsia that was in the process of rethinking Hinduism in light of the onslaught of British colonial culture.

In one way, however, Naren and Ramakrishna were very much alike. Neither seeker was content with the mechanical practice of religion as a habit based solely on custom, but instead longed for the direct experience of the divine. Naren went to the numerous wise and educated persons active in Kolkata in his time with the question, “Have you seen God?” Each answered in the negative.

Finally, one of his philosophy teachers, a Scottish clergyman named William Hastie, recommended that he seek out Ramakrishna, the priest of Kali at Dakshineshwar. Naren did so. When he asked Ramakrishna, “Have you seen God?” he was taken aback when Ramakrishna replied, without any hesitation, “Yes, only more vividly than I am seeing you now.” Though he at first thought Ramakrishna to be a madman, he soon became his pre-eminent disciple.

The emblem of the Ramakrishna Order

After Ramakrishna’s passing, Naren organized all the young men who had been Ramakrishna’s closest disciples into the Ramakrishna Order – a community of monks dedicated to the service of humanity and to spreading the message of their master far and wide. Taking the monastic name of Swami Vivekananda, Naren addressed the Parliament of the World’s Religions in Chicago just seven years after Ramakrishna's passing. He was the first Hindu monk to travel to the West and initiate disciples in the practice of Vedanta, the philosophy that served as his vehicle for communicating his master’s teaching of universal acceptance.

Quoting the Hindu scriptures, Vivekananda proclaimed in Chicago, “As the different streams having their sources in different places all mingle their water in the sea, so, O Lord, the different paths which men take through different tendencies, various though they appear, crooked or straight, all lead to Thee,” and, “Whosoever comes to Me, through whatsoever form, I reach him; all men are struggling through paths which in the end lead to me.” (From Swami Vivekananda, Complete Works: Volume One, p. 3)

These statements of religious harmony and equality were radical when Vivekananda first shared them with the world on – ironically – September 11, 1893. Sadly they remain, for many, radical even today in a world seemingly as divided by ethnic and religious hatred as ever. Even more radical was the teacher behind them, Sri Ramakrishna, a man infused with the spiritual temerity to seek the direct vision of the divine, not simply through the medium of one religion or practice, but through as many as he could. Likewise was the disciple who shared this vision with the world, Swami Vivekananda, who had the courage to speak to Westerners as equals at a time when India was still under the crushing heal of British imperialism. Vivekananda first addressed the Parliament of the World's Religions as “Sisters and Brothers of America” and straightway received a standing ovation of several minutes, reported the New York Times.

Together, these two figures acted as midwives of the interfaith movement, inspiring people of many traditions to think of their differences in a new way and to act upon this vision of harmony.