By Tarunjit Singh Butalia

WHAT WE EAT, WHAT WE BELIEVE

I fondly remember one of my best friends from high school in northern India in the early 1980s, Sher Ali Khan. He was a devout Muslim.

While in ninth grade, Sher Ali called me over to his home for the Islamic festival of Eid. The food at the table was overflowing and beautifully decorated. However, a dilemma faced me. All the meat on the table was halal – prepared according to a special religious technique of preparation in the Islamic faith. I, as a Sikh, was forbidden to eat halal meat due to the Sikh Rehat Maryada (Principles of Sikh Living). So I chose to stay a silent vegetarian that day, partaking only of vegetables and sweets.

A couple of months later, he was over at our home for dinner, and we had cooked the meat without any religious preparation. Since the meat was not halal, Sher Ali became a vegetarian for that meal.

At that time I thought that our religions were getting in the way of our friendship. But as I reflect on it now, it seems that we were learning how to negotiate our religious differences.

In 1989, I came to the United States to pursue my PhD degree at The Ohio State University. I was at least an ocean and continent away from my parents and family.

As I began my academic career in the United States, the first question I asked myself was, “Do I even want to continue being religious?” After significant introspection, the answer became clear: yes, I wanted to be religious. This was followed by another question: “What religious tradition should I follow?”

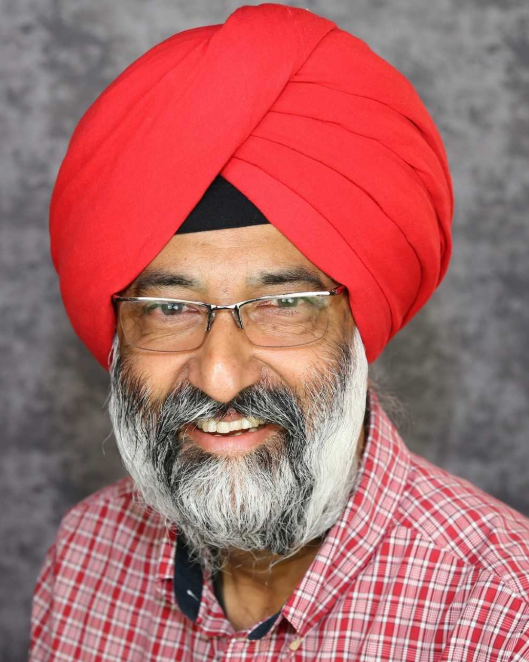

Dr. Butalia never met his Catholic counselor again, but here greets Pope Benedict XVI as a Sikh interfaith activist. – Photo: Tarunjit Singh Butalia

I approached a local member of the Catholic clergy and asked for his advice on what religious path to consider pursuing. His response surprised me. He asked me to look deeply into the faith I had grown up in and asked me to come back to him after giving my faith one more chance.

As you may have guessed by now, I never went back to that priest. But I am indebted to him for his advice. Here was someone from another religious tradition that helped me to grow in my own religious tradition. His advice on spirituality transcended the boundaries of religion.

Today, as I reflect on my friendship with my Muslim high school friend and the Catholic spiritual adviser, it is clear to me that the many diverse religions of the world are complementary to each other and not in competition with each other. These are values upon which the interfaith movement is built.

Mutual respect and understanding across religious boundaries is a fundamental need of humanity today. The interfaith and interreligious movements are at a critical juncture. How do we expand the circle of those engaged in this work, and how do we deepen the engagement of those already involved? These are the issues that the interfaith movement needs to address so we can make this world a safer and more just place for our children and grandchildren.

A version of this essay was originally published in the Parliament Blog, June 1, 2011.