By Rachael Watcher

The Modern-Indigenous Divide

In 2004 I attended the Parliament of the World's Religions in Barcelona, Spain. When the appointed translation services broke down during the explanations of indigenous rites being enacted, I was asked to help translate. I speak Spanish and come from an indigenous-related spiritual tradition. So began my journey into the world of interfaith relationships.

Hard lessons began almost immediately. To start with, speaking Spanish does not necessarily qualify you to “speak” Spanish. My background is construction contracting, working with blue-collar workers. My vocabulary was totally unprepared for translating religious dialogue, ritual details, or different ideas of the Sacred. Yet, because I practice a religion that is nature based, believes in magic, and is orthopraxic – that is, practice-based rather than faith-based – I found myself explaining ritual actions and indigenous rites to Eurocentric Abrahamic folks. What a divide!

I was grateful for the dictionary I’d installed in my phone. The device never left my hand. I understood the questions being asked, and understood how to phrase them for the practitioners. But over and over I lacked the Spanish vocabulary necessary to translate the answers. Simple questions became lengthy discussions in order for us all to understand one another.

In 2009 at the Parliament in Melbourne, Australia, hoping that my Spanish vocabulary had sufficiently improved, I decided the best use of my time in service was to help an indigenous friend, Raul, from Argentina make his way around the Parliament. There was no translation of any kind provided so I was with him constantly from breakfast to dinner except when one or two other friends accompanied him for brief periods of time.

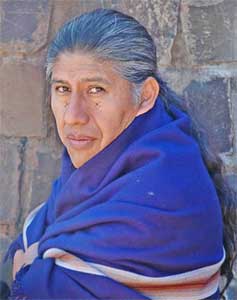

Raul

His interests were starkly different than mine which actually allowed me to focus on translation rather than on our own discussions. His indigeneity quickly became apparent in his frustration with the schedule, time constraints, and often with the manner in which topics were handled. Certainly he did not like sitting in rows where he could see no one but the persons on either side of him, listening to one person pontificate without input from the rest of the room.

In one case there was some serious misrepresentation of indigenous dialogue. Instead of staying until the end of the presentation to speak up and question what he saw as a clear violation of trust, he demanded that we leave and go have lunch. I said his voice was important, that he needed to stay and speak out. He said he’d give no more time to what he perceived as an injustice. He steadfastly refused to speak of it again, even when asked to write a letter to the board of the presenting organization. I said he could not expect change if he did not speak out for it, but he was clear, and he was not alone. In trying to gather other indigenous points of view we ran into the same wall; only those sufficiently inculcated within the dominant cultural and its way made it into the dialogue. He gave me permission to speak on his behalf, though I could not make clear to him that my voice on his behalf would carry no weight.

A Different Sense of Time

My next big lesson was becoming comfortable with a different sense of time – something my colleague Don Frew and I learned in planning a visit to indigenous religious leaders in Peru. Indigenous peoples traditionally live in a world where the past no longer matters and the future does not yet exist. One lives in an ‘ever present’ world where everything happens in its own time. So there is no urgency about doing anything, no need to schedule something later. Indigenous time has been called circular time, as opposed to linear time, which governs most of Western culture.

Part of the group of indigenous leaders brought together by United Religions Initiative in Peru.

You may decide that tomorrow is a good time for a meeting in circular time. The idea that airplane tickets and travel plans must be made ahead of time, particularly when working with a tiny budget, doesn’t register. This became clear in the “off again, on again” planning of our trip to Peru. Six weeks out we heard the meeting was canceled. A week later it was back on, but set just two weeks away. We responded that the short notice made it impossible for us to attend from North America, so it was again rescheduled. This went on for a couple more rounds, until we finally nailed down a date.

Arriving in Ayacucho, Peru, the first order of business for our indigenous friends was to secure a website. I had determined to listen quietly and stay in the background, which turned out to be impossible. They knew they wanted a website but had no idea how to set one up or what it would cost. It was magic, in its unknowns. I ended up agreeing to build a simple website. I bought the name for ten bucks, took an hour to design it, and posted it to a URL on a friend’s server at no charge. That web page is still up. Getting updates is almost impossible, so it remains much as it began and they remain delighted with it. The simple act of having their own web presence made them real in ways impossible to explain to anyone from a technical culture.

Our Peruvian conference included non-indigenous attendees from the sponsoring organization, the United Religions Initiative. Forty indigenous people were at the table, along with Elder Don Frew and myself, an assisting Mayan friend, and two Jewish gentlemen who were Eurocentric culturally, rather than indigenous. This rich mix came with its own lessons.

The indigenous meeting procedure is to pass the right to speak, in this case indicated by the microphone, around the room. Each person speaks about anything and everything that he or she wishes to discuss without interruption or questions. When they are done, they pass the mike, generally along with a big bag of coca leaves. The next person repeats this process. Sometimes they talk about issues raised by the previous speaker, sometimes about other issues. This process, a bit unorganized, gradually builds consensus. Since time has no measured meaning, a topic is explored to everyone’s satisfaction and finally disappears. At that point everyone understands that there is nothing more to discuss and ‘agreement’ has been reached on the matter.

Don and I belong to a religious community that uses consensus-based decision making, so we had no trouble following the indigenous process unfold. Our Eurocentric guests had a harder time. One, upon receiving the mike, repeatedly invoked Robert’s Rules of Order and asked that they be used during our time together. Everyone politely agreed. More than once. As soon as the mike passed on, discussion continued unaltered in its organic format, unabated. By the end of the day several decisions had been made, with everyone well-satisfied at our progress, save for our Jewish friends who missed the implicit decisions when issues were dropped.

Writing “it” Down

Alejandrino

Written communication is another learning arena. The indigenous approach to making a report is to go back to a project’s earliest beginning, discussing everything possible about it up to the present time, before getting to the gist of the report. When asked to write a report on last year’s activities of the Global Indigenous Initiative (GII), my friend Alejandrino from Ayacucho de Peru, wanted to tell GII’s entire history, detail by detail. It took a week to winnow down his report to the pertinent information about the group today. Alejandrino never really understood the edited result. He felt that it was so incomplete as to be incomprehensible. Email can be equally confusing when questions are answered tangentially rather than directly.

Beware the judgment that makes our culture or theirs the better. Humankind needs us all, and spending the time to listen, to translate carefully, enriches us all. High quality dialogue facilitates learning for everyone. I have gained a great deal from these ‘translation’ years, going back to what I learned at the start – that a common language does not guarantee common understanding. For South American indigenous people, all religion is referred to as “Catholic,” which is a terrific place to start the translation task.

I come to the table to listen, knowing that the heart of a problem does not always lie at its root. The issue with the web page was not having one but knowing that they had one. Whatever the subject, an historical recitation should not be overlooked in order to speed a process. That look back is a way of honoring all of the people and work that have gone before, not forgetting it, which so often happens on our side of this cultural divide. The divide will endure, should endure; but it is good to know that there are ‘translators’ on both sides who are reaching out with determination and patience to develop constructive relationships among us all.